What the It movies are really about and why the sequel is superior

The idea that the first It movie is better than the sequel is complete poppycock, says Luke Buckmaster, who explores what these twisted horror films are really about.

What is the difference between remembering something, and never forgetting? It: Chapter Two implies it is a matter of active versus passive: the latter lingering in the back of the mind, and the former requiring conscious thought. In the universe of Stephen King, whose 1986 novel the film adapts, what lingers is not, of course, something sweet but poignant, like a couple of visions from my own childhood – such as a basketball ring broken from too much use, and a LEGO man minus a limb.

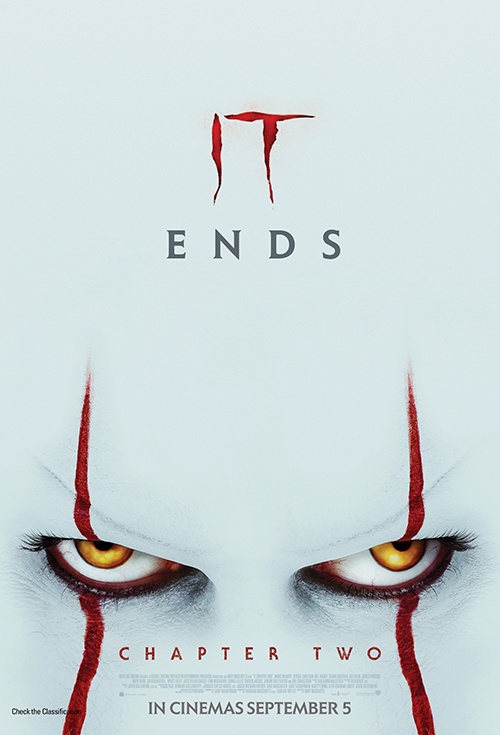

No. What lingers is a malevolent force in the form of a hideous sewer-dwelling clown. He is Pennywise (Bill Skarsgard), whose appearance actually sounds quite nice in written form: with his elastic waistband pants, frilly collars, red pom poms, lace bell sleeves, and, oh yeah, the gleaming eyes of satan’s spawn and buck teeth that transform into fang-like instruments of death. He, or “It,” haunted a bunch of children in the 80s who called themselves “The Losers” and returns to menace said Losers again in adulthood.

Sign up for Flicks updates

This motley group – which includes stand-up comedian Richie (Bill Hader), fashion designer Beverly (Jessica Chastain) and a mystery novelist with a stutter, Bill (James McEvoy) – never, surprise surprise, forgot that soul-sucking makeup-caked thing from the gutter. However, as the years rolled by, the further they moved away from their home town of Derry the more their memories of the feral, vaudevillian-looking apparition faded.

Mike (Isaiah Mustafa – the guy from the Old Spice commercials, made to look less hot) never left, settling into life as the town librarian. So his memories of Pennywise are more acute. Or perhaps he is simply reminded of his childhood circumstances more often, thus engaged more frequently in the active process of remembering.

In any event the damn clown is back, gobbling up a new generation of cherub-cheeked pipsqueaks from beneath the bleacher’s seats. The grown-up Losers are each telephoned by Mike, who delivers what struck me as a rather tough sales pitch: he’s got to convince them to head back to good ol’ Derry for version 2.0 of their own personal hell. The clown knows their deepest fears and insecurities, so the stuff he throws at them is a sort of Room 101 through a fun house mirror. George Orwell gone carnie.

To their credit the group exhibit considerable derring-do, trotting back home to soil their pants and lay their souls on the line. A key stretch of the film takes a horror movie cliché – the “let’s split up rather than stay together” chestnut – and turns it into a series of vignettes in which the characters confront unresolved aspects of their childhood. The point is made that sinister forces such as a violent, abusive, yeti-like bastard of a father may not be physically alive anymore, but still exist in the form of intense feelings in the minds of victims, in this case Beverly (his daughter).

That message is core to understanding what all the screechingly loud jiggery-pokery summoned by director Andy Muschietti (who also helmed the first movie) is about. Gather in close and talk about your feelings, friends, because Pennywise equals unresolved emotions: a wound or a series of wounds that haven’t healed. To put it another way, the core message of this film, and the novel, is that the psychological issues we fail to deal with as youth return to haunt us as adults.

That essential part of the text was absent from It: Chapter One. Set entirely when the adults were kids, it had no means to look back and contemplate formative trauma. The film was the trauma, not an exploration of it. When the producers took Stephen King’s book and chopped it in half, the buggers removed the only thing that gave it real substance.

It: Chapter Two, at least, really does want to mean something, despite its obvious flaws. Several of these relate to an indefensively long 169 minute running time, including numerous extraneous sequences and tacked-on voice-over narration. Props to the filmmakers for engineering some genuinely weird visual effects, such as hagged lady-monsters who make the woman from Room 237 look like Miss Universe, and fortune cookies that contain – shall we say – not entirely optimistic messages.

The best parts of the film are very short: moments that fold more than one timeline into a single sequence, expressing core themes visually. On several occasions Muschietti weaves the same character’s childhood and adult experiences into the same scene, and even has a character facing off against a version of their younger selves.

Other moments use visual transitions to change time during unbroken images. There are shots of drops of blood that keep dripping onto the frame even as the scene changes time and context, for instance, which is a fabulous effect – implying this godforsaken film has been glued together with body fluid. In one clever shot the camera follows a red balloon going up (leaving the scene) then coming down (into a different scene). There are others of similar ingenuity.

Pity about that running time blow-out, because the more you watch It: Chapter Two the more you acclimatize to its weirdness. Pity also that the first film was so utterly derivative. At least this one has something that vaguely resembles a point. I was very fond of the moment when Pennywise stares at one of the characters and exclaims: “look at you, all grown up!” Whether remembered or never forgotten, he’s always been there.

More

See All