Why Mindhunter is a perfect example of David Fincher’s obsessive excellence

The second season of the engrossing serial killer thriller Mindhunter recently arrived on Netflix. Sarah Ward explores why it’s the perfect show for the great director David Fincher, whose thrillers include Seven and Zodiac.

When Charlize Theron gave David Fincher a copy of Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit a decade ago, it must’ve seemed an easy choice. That’s no slight on Theron’s gifting abilities; she just knew her audience. Co-written by John E. Douglas, the non-fiction book details the retired agent’s time interviewing notorious serial killers and mass murderers – a subject that, as seen in Seven and Zodiac, was already close to Fincher’s heart. The next step was obvious. The subject matter screamed for a screen adaptation and, although it took eight years, Mindhunter was born.

Fincher is credited as one of the Netflix series’ executive producer, rather than its creator; however Mindhunter couldn’t better fit into his oeuvre. Visually and tonally, his stamp is all over the show. It blazes brightly in the seven installments he has directed so far, out of a possible 19, with the filmmaker opening each of the show’s two seasons to-date with a group of episodes – two in the first season, three in the second – that firmly set the mood. In Mindhunter’s debut 2017 run, he also returned for the concluding pair of episodes, wrapping up the initial batch of ten chapters as it began.

From Fincher’s precise, detail-oriented images, his penchant for cool hues, his keen eye for texture in for both faces and wide spaces, and his patient, lingering shots comes the show’s house style, too. Even when other directors have taken the reins, including for multiple episodes each, his imprint remains. Again, that’s not a criticism of Senna’s Asia Kapadia, A Hijacking’s Tobias Lindholm, Chopper’s Andrew Dominik and Devil in a Blue Dress’ Carl Franklin. They are all accomplished filmmakers with their own impressive bodies of work. But to watch Mindhunter is to always see Fincher’s vision – as spied in Seven and Zodiac, and even in fellow crime thrillers such as The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl – bubbling away underneath.

As much as Mindhunter always looks like it’s under Fincher’s thrall, his influence shines brightest elsewhere. The series isn’t just fascinated with serial killers, or with twisty crime tales, but with obsession. It ruminates not only over those who kill, but on the procedure behind and meticulousness inherent in their horrific acts – and, crucially, in the resulting investigations into their deeds as well.

Understanding what drives multiple murderers, the traits and personality tics they share, the processes they follow, and the mindsets and behaviours they’re compelled to act upon is the job of Mindhunter’s special agents Holden Ford (Jonathan Groff) and Bill Tench (Holt McCallany), in conjunction with psychology professor Wendy Carr (Anna Torv), as they interview everyone from Ed Kemper to David Berkowitz to Charles Manson. Demonstrating the comparable level of fixation required to track, interrogate, analyse and profile serial killers becomes, over the show’s first two seasons, its overarching achievement.

This isn’t new territory for Fincher. Rather, in building upon his back catalogue not just aesthetically but thematically, he’s as calculating as any character within his frames. He doesn’t conflate killers with detectives – not in Seven, Zodiac or Mindhunter – but instead delves deep into the one element that binds the two: obsessiveness. Given his fondness for returning to the topic, he’s clearly excavating an aspect of his own personality in the process. Again and again, he spins stories about people consumed by murder and by hunting down murderers, all while proving just as consumed by the act of telling such tales.

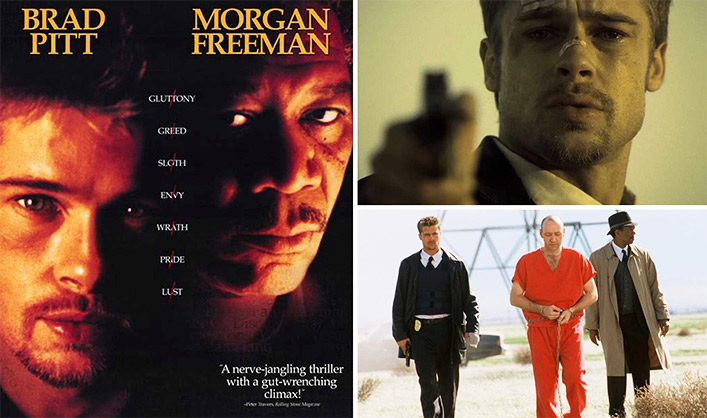

Although Alien 3 will always remain Fincher’s first feature credit, it was Seven that truly announced his arrival as a filmmaker to watch – and trumpeted his obsession with obsessions. The 1995 movie also established Fincher’s determination to unfurl intricate crimes through a diligent investigatory lens.

As a killer stages elaborate deaths inspired by the seven deadly sins, Seven assesses, evaluates and unpacks each murder via the work of detectives William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and David Mills (Brad Pitt), charting the culprit’s grisly yet elaborate deeds through the cops’ own exacting examination. Indeed, while John Doe (Kevin Spacey) goes out of his way to bring his pursuers into his killing spree, as immortalised in the film’s famous “finale, Fincher’s portrait of their intertwined fervour already did the job.

What Seven started, Zodiac expanded upon, this time via a notorious real-life case. The 2007 drama’s true-crime focal point let Fincher dig further into the idea of obsession, and convey it clearly to his audience, by recreating details that many have obsessed over for decades. Zodiac depicts the toll of fixating on the titular serial killer, not in fictionalised or general terms, but on three figures who lived through it.

As the murderer terrorises the San Francisco Bay area across the late 1960s and early 1970s, detective Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo), journalist Paul Avery (Robert Downey Jr) and cartoonist Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) immerse themselves in the case to the point of being haunted by it. Fincher painstakingly relays their efforts, as well as the repercussions.

With Seven and Zodiac, a pattern emerged. Both movies feature similar investigative minutiae, from following leads, to scouring library materials, to tracking data on walls and boards. Of course, most investigations feature the same investigative techniques – in the pre-internet era, at least. Obsession, in the case of lawmen chasing criminals and reporters covering crimes, is a tangible affair. Perhaps that’s why, even as technology has progressed, Fincher has largely kept his serial killer films in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. (In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl, he paired more modern investigation tactics with journalists, hackers and cops possessed by their own searches for answers, but also tied them to a noticeably different kind of narrative).

Thanks to the groundwork laid by Fincher’s films, Mindhunter feels like a culmination. After decades diving into the same realm and puzzling the right pieces together, he’s now sinking as far into his obsession as possible. And, within its specific storyline, the series shows its own version of that process. Ford, Tench and Carr are given the chance to indulge their firm field of interest, to probe it again and again, and to tackle it from different angles. That’s the Fincher process: examine, fixate, deconstruct, repeat. It’s one that, through serial killer thrillers, he’s perfectly positioned to keep obsessing over.