The fascinating story trend of some of this era’s most mind-bending films and TV

Productions such as La Belle Époque, The Truman Show and Westworld belong to a fascinating genre that is so unusual it doesn’t even have a name. Luke Buckmaster explains what it is—and why you should be paying attention.

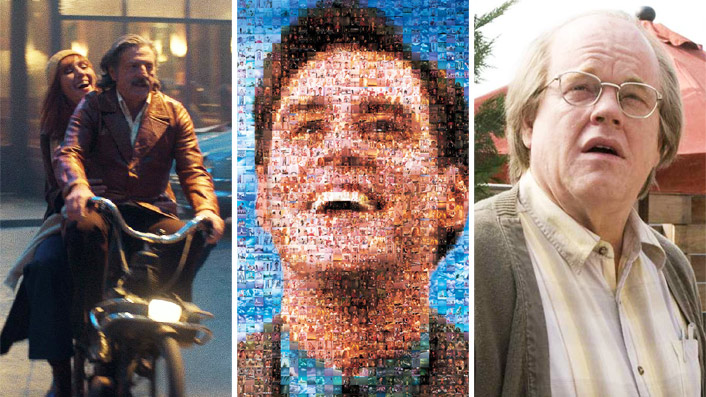

In writer/director Nicolas Bedos’ high concept French comedy La Belle Époque (now playing in cinemas), a company called Time Travellers provides real-world narrative experiences set in any period their clients choose. Want to sip absinthe at a honky-tonk with Ernest Hemingway? Or spend an evening in Hitler’s bunker with the Führer? No worries. Cough up the coin and they’ll make it happen.

See also

* All movies currently playing in cinemas

* All new streaming movies & series

This very fine and shrewd film made me think about other productions that contemplate these kinds of narrative experiences—or reality simulations, shall we say—in interesting ways, from The Truman Show to The Game, Westworld and the recent Dispatches from Elsewhere. I’m fascinated by this genre, if we can call it one, since I’m pretty sure it doesn’t have a name and the ‘reality simulator’ story doesn’t exactly sound sexy.

A little more on La Belle Époque, before we move on. The Time Travellers’ immersive theatre-like experiences—which boast impressive sets and professional actors—are stage managed by a Christof-esque director (Guillaume Canet), who delivers cues to his performers via earpieces. The experience the protagonist Victor (Daniel Auteuil) requests is a recreation of the day he met his wife (who is played by an actor, Doria Tillier, playing an actor playing his wife) in a Lyon café in 1974.

The execution of this fantasy, which involves a purpose-built set, is beautiful and detailed, but the protagonist is under no illusions. Victor knows this is a fantasy, the same way visitors to Westworld understand they are engaging in a contrived spectacle with robots fulfilling the role of narrative agents.

Bedos is making a point here about the nature of immersion: how it relies less on convincing production values (in whatever medium i.e. film, TV, virtual reality) than a willingness on behalf of the observer or participant to embrace imaginative worlds. This process has a name: suspension of disbelief.

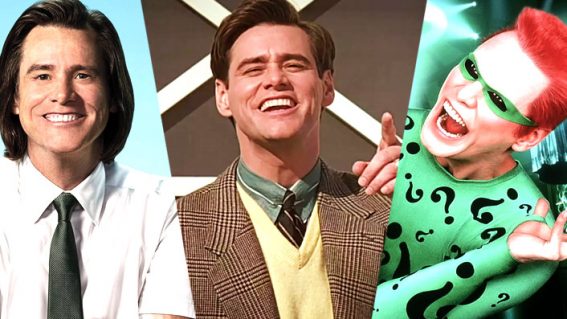

Some films have created compelling situations by exploring the inversion of that idea, telling stories about the horror of being unable to determine narrative constructs—where reality ends and contrived fantasy begins. The most famous example is probably Peter Weir’s The Truman Show—that magnificent, big-thinking 1998 film starring Jim Carrey as an insurance salesman who is unaware that his life is a TV sensation, and becomes determined to break free of the manufactured simulation governing his existence.

In David Fincher’s 1997 thriller The Game, Michael Douglas is a wealthy investment banker embroiled in the titular experience, becoming completely (and understandably) paranoid—running for his life (supposedly) and being entombed alive in a Mexican cemetery (for real). He is told from the outset that he is participating in a ‘game’, but the content creators cleverly make him believe it is no longer a fantasy but an actual attempt to rob him of his money and reputation.

More recently, Prime Video’s kooky series Dispatches from Elsewhere (read my thoughts on it here) presented a narrative inspired by a real-life ‘alternate reality game’ that took place between 2008 and 2011, tantalisingly described by this Vice article as “living metafiction.” That word—“metafiction”—is a good way to describe the curly events in Charlie Kaufman’s mind-bending drama Synecdoche, New York, in which an acclaimed theatre director (Philip Seymour Hoffman) constructs a massive set and fills it with actors living out scripted lives.

Each of these productions depicts narrative experiences that challenge traditional notions of authorship. Interactivity is a key feature. For a very long time—since the days of stories recited around campfires—the dominant form of narrative has relied on a teller-listener relationship. The foundation of these experiences is something else: a builder-participant paradigm, emphasising story worlds as much as storytelling.

Perhaps that’s why I am so compelled by these narratives-within-narratives: because they reflect a world slowly moving away from the age-old concept of stories constituting single, non-interactive, unalterable experiences. Artistic creations involving participation have existed for a very long time (from tribal rituals to participatory theatre) but we are now seeing interesting versions of narrative participation everywhere in the real world, unified by that one word: experience.

In Escape Rooms, for instance, in which players collaborate to solve puzzles while the clock is ticking. Or ‘dining in the dark‘ restaurants, which are exactly how they sound: about paying for the pleasure to eat with no lights on. Or ‘secret cinema‘ events during which films are screened, accompanied by actors and mini performances, and viewers who dress up as characters from the narrative world. Or even an experience that reproduces the sensation (if you can call it that) of being in a plane crash.

Experience-based events of different varieties have been around for a long time (i.e. theme parks, dinner theatre, love hotels, paintball) but these ones belong to something different. Something authors Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore prophetically described, in a 1998 article for Harvard Business Review, as “the experience economy.” The premise of their article, which is well worth a read, is that experiences comprise “a distinct economic offering, as different from services as services are from goods.”

But could this economy be part of something much bigger: a shift from the Information Age to an Experiential Age? Virtual reality enthusiasts have floated the possibility for a while. It doesn’t appear to have taken hold in broader circles, but from a certain point of view—in our digitally connected and internet obsessed world—we see evidence of information lethargy everywhere. As the late Jean Baudrillard put it, in words that are even truer now than they were when first printed in 1981: “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.” And where (Baudrillard again) “meaning is lost and devoured faster that it can be re-injected.”

In these noisy and chaotic times, we all feel information overload. We all understand that hitting the bottom of any online article reaches the end of nothing—just another cycle in an infinite scroll; another flex in a roiling tide of information. Perhaps people in the future will value experience as much as they value information. Those experiences will come in many forms, including virtual and augmented realities, theme parks like Westworld, or even a ‘reality simulator’ like the kind in La Belle Époque.