Against the odds, Baz Luhrmann’s Faraway Downs is actually pretty bloody decent

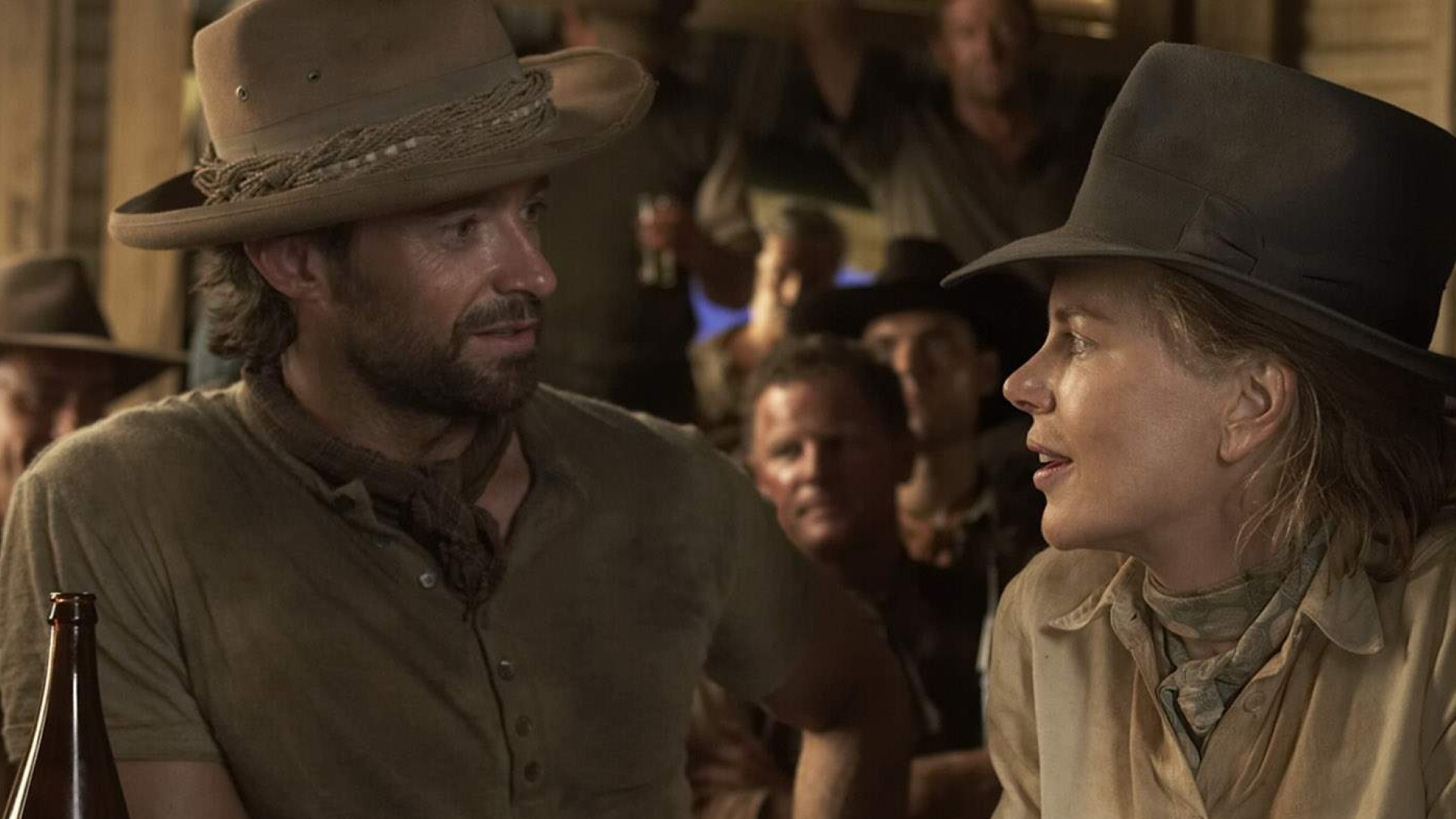

Baz Luhrmann’s oft-panned 2008 epic Australia, starring Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman, has been expanded as mini-series Faraway Downs. Luhrmann has managed to turn a forgettable film into a flawed but dazzling piece of television, writes Amelia Berry.

They call Australia ‘the lucky country’. A land without class distinction, overflowing with opportunity. Where you can get paid well for your work, and still have time left over for sports, leisure, or time with the kids. Of course, from the infamous White Australia policy, to the recent abject failure of the Voice Referendum, the truth is that these privileges have always been contingent on the colour of your skin.

This dark contradiction at the heart of Australian national identity forms the basis of Baz Luhrmann’s 2008 adventure romance Australia—an operatic vision of Australia’s Northern Territory in the lead up to the bombing of Darwin in 1942. Self-consciously modelled on the epics of old Hollywood, Luhrmann builds his story of love, death, and despair from a heady blend of cattle ranching, The Wizard of Oz, and a smattering of Aboriginal song and story traditions.

The result is, frankly, a mess. Struggling to fit its sweeping narrative into a still unwieldy 165 minutes, it lurches disconcertingly from set-piece to set-piece. Despite themselves, Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman can’t manage to flesh out their thinly written characters, overwhelmed as they are by pulpy melodrama and Luhrmann’s characteristic camp flourishes.

While this kitsch does succeed in lending a degree of charm to the film, it can’t help but sit uncomfortably alongside the plot’s central concern with The Stolen Generations—the Australian government’s programme of abducting Aboriginal children and placing them in white families or institutions.

Australia did decently at the box office, but received mixed reviews and landed with a dull thud in the public consciousness. One Australian reviewer accused the Murdoch press of manipulating coverage of the film in its papers (can’t get more true blue Aussie than that), and even in Roger Ebert’s largely positive review of the film, he noted that “Baz Luhrmann dreamed of making the Australian Gone with the Wind, and so he has, with much of that film’s lush epic beauty and some of the same awkwardness with a national legacy of racism.”

Now, in the age of the ‘Snyder cut’, Luhrmann has been given the chance to revisit Australia—recutting the existing footage, bringing in deleted scenes, and transforming it into a six-episode limited series named after the film’s plot-crucial cattle station, Faraway Downs.

So… Who asked for this? How could this possibly be worth watching? Who thought that Australia could be made better by being even longer?

Well, against the odds, Faraway Downs is actually pretty bloody decent. At the very least, it’s a good sight better than Australia. While it carries over some of the issues of the original—particularly in its awkward reckoning with race—all in all it’s better told, more exciting, more moving, and with the new cut recasting the performances in a whole new light.

To give a brief overview of a pretty involved story: Lady Sarah Ashley (Nicole Kidman) is an English aristocrat, come to Australia to divorce her absentee husband. When she arrives, she finds her husband dead, Fletcher the station manager (David Wenham aka Faramir aka Diver Dan from Seachange) stealing her husband’s cattle, and the police beating down her door to find mixed-race Aboriginal boy Nullah (Brandon Walters).

So, she teams up with Nullah and mysterious hunk The Drover (Hugh Jackman) to drive their cattle to Darwin for sale. Though they quickly become a family to each other, they are haunted by the nefarious Fletcher, and finally, as Japanese bombs fall on Darwin, they must face down the racial animus that threatens to tear them apart.

It’s a story that benefits a lot simply from being broken into episodes, allowing it more room for the tonal shifts and plot pivots that felt so jarring and momentum-starved in the original film.

While the characters don’t necessarily have more dimension, they’re much more cleanly drawn, with Luhrmann able to add more context for their actions and relationships through cut footage. Kidman’s screwball dame/war damsel performance makes so much more sense in this cut, and is honestly surprisingly well done.

But it’s not just what’s added. The Drover, especially, has several ‘complicating’ lines and scenes cut (largely those teasing his relationships with Aboriginal women). It’s a move that works well for the material—these are big, swooning archetypes and edging away from ‘realism’ only makes that work better as an artistic choice.

Playing up this operatic mode with its starkly cast heroes and villains does so much to make Faraway Downs into the Down Under Casablanca that Luhrmann clearly always wanted it to be. Sadly though, it’s a form of storytelling that can’t help but do a disservice to its Aboriginal characters.

Brandon Walters’ performance as Nullah is remarkable—the emotional core of the film. Likewise, the legendary David Gulpilil is an overwhelmingly compelling presence on the screen. Near the end of the series, when his character stands in the street as Darwin burns, it’s a performance that’s masterful in its stillness. And yet, Faraway Downs can’t really let these characters be more than magical, mysterious, other.

At the same time, their stories are too often sidelined in favour of the white leads. Luhrmann clearly wants to do some truth-telling about Australia’s murderous history, but his primary concern is with resuscitating the character of the rugged outback individualist, recasting the Australian frontiersman as an anti-racist hero. Perhaps in giving this version of his story a more tragic ending, Luhrmann is signalling a change in his attitude to the Australian colonial project—regardless, as a glossy/campy American-style romance, it can’t help but feel like it’s pulling its punches.

Faraway Downs was always going to be a strange beast, but in teasing out the most compelling threads from the tangle that was Australia, Luhrmann has managed to turn a forgettable film into a flawed but dazzling piece of television.