Biopic The Apprentice can’t quite master Donald Trump’s 1970s/80s ascendancy

Sebastian Stan is Donald J. Trump in The Apprentice, charting the former guy’s New York ascendency in the 70s and 80s, and his relationship with mentor Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong). Rory Doherty bites into the Big Apple biopic at Cannes.

As Donald Trump, Sebastian Stan gives an interesting performance. That may not be as gratifying or extreme an assessment as you’d expect from a fairly popular actor playing the most well-known person on the planet right now, especially because Stan is trying to give a straight dramatic take of an incredibly impersonated public figure.

For The Apprentice’s depiction of Trump’s ascendency through New York’s power rankings in the 70s and 80s, Stan makes the same choices as many comic impersonators—find some key physical and vocal traits, embellish them, filter every reaction and sentence through them. We see the trumpeted lips, the frequently hanging mouth, the nodding head and moving hands; every time Stan drops an “interesting” or “spectacular” it reminds us of parody.

But the fact that Stan plays it so straight gives his young Trump performance an uncanny quality, where we’re constantly aware of his effort, of the gap between performer and a public figure who has always been both transparent and baffling. This uncanny effect is where the film best excels as it charts Trump’s mentorship with Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong), a tough lawyer for the super-rich and powerful. It’s disappointing, then, that these glimpses of a thornier, eerier film are restricted only to surface-level vibes; The Apprentice only seeks experimentation and ambiguity as a veneer on top of a rote, unimaginative portrait of the real estate magnate’s psychology.

Iranian-Danish director Ali Abbasi’s career to date suggests that his origin story of Donald J. Trump would be a touch more evocative than it ends up being. His debut Shelley was overshadowed by his sophomore feature Border, about a Swedish troll with exceptionally heightened senses working as a border guard for quietly discriminatory humans, and his serial killer noir Holy Spider divided audiences with its grisly, too-pulpy take on a real case of gendered violence in Iran.

He stepped into English-language fare with the final two episodes of last year’s The Last of Us, a show that similarly tries to straddle prestige drama and blatant genre thrills. But the most horror-coded element of The Apprentice are the long, probing shots of Roy Cohn’s vacant but piercing eyes, which silently plead for Trump’s story to go deeper into the fascismo-capitalist psyche than Gabriel Sherman’s script will allow.

Strong’s performance of Cohn, a bullish, conniving fixer who helped McCarthy oust suspected communists, is so magnetic that it threatens to eat the first half of the film—but when Trump’s reach starts over-extending in the 80s and Cohn is pushed to the sidelines, Strong’s chemistry with Stan is sorely missed. Chemistry may not be the most appropriate word: each actor leans heavily into their character’s theatricality that they give completely opposing energies as they showcase their craven power lust and swollen egos. Trump is all off-putting affectation and projected power; Cohn’s black heart can be seen in every accented line he speaks.

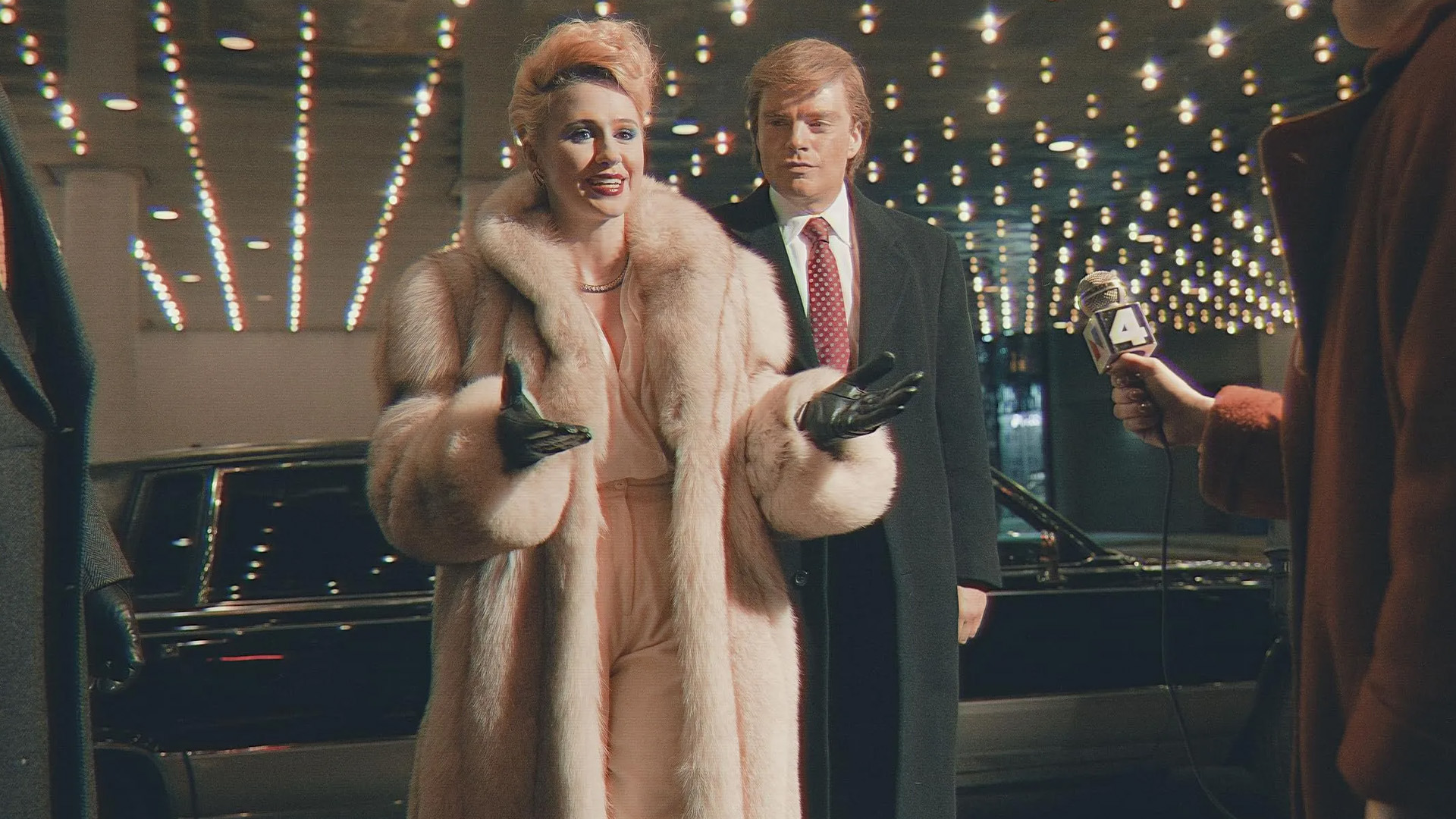

But The Apprentice only lets us enjoy their cursed dynamic for as long as Trump and Cohn were close allies—the late 70s into early 80s—switching focus to Trump’s first wife Ivana (Maria Bakalova) for the second half. The switch between Trump’s pursuit and subsequent disinterest in his wife is expressed with impact and clarity in disgusting comments and shocking bursts of violence, but Abbasi doesn’t show nearly the same interest in tapping into the suppressed emotions of this relationship as he does with Cohn. The director is happy to hang Bakalova’s competent performance out to dry with the usual tropes neglected and abused wives face in biopics (clearly what Ivana experiences is extreme).

Yes, Donald Trump gets to pratfall quite spectacularly. Yes, one creepy Roy Cohn interview where he denies his illness is comically contradicted with disgustingly high-quality cameras. Yes, Donald Trump’s implied complicity in his brother’s suicide is touched on with uncomfortable pathos. But The Apprentice lacks instincts that make it feel distinct from the same, tired voices that have been decrying Trump for a decade, uninterested to go any deeper and content that we’ll be shaken by the respectable, arthouse-minded sheen on its predictable narrativisation of his early career.

One visual choice indicates Abbasi is at least curious about altering our perspective—in the 80s, scenes come with a visible video crackle to them, as if they were shot by a era-appropriate consumer-grade camcorder, and the difference in light quality, depth of field, and skin texture reminds the audience of their status as an observer in a room that looks somehow off and unusual.

But elsewhere The Apprentice struggles to address how we’ve spent nearly ten years, on a mass scale, accessing and critiquing Trump from an outsider perspective, which has defined how we explore him in fiction. This voyeuristic fascination perhaps shouldn’t produce a film interrogating him, but rather be interrogated itself. Why make an origin story of Trump, other than because it will attract attention along the way? By making the perspective so narrow, The Apprentice backs itself into a politically ineffective corner.

Originally published by Flicks on May 23, 2024