Deerskin is one of the best and sharpest comedies of the year

Now playing in select cinemas, French director Quentin Dupieux’s bizarre film about a man obsessed with his own jacket is a fiendishly clever comedy, says critic Luke Buckmaster.

In essence Deerskin is about a man who really, really likes his jacket—so much that he decides nobody else should be allowed to wear any jacket in any circumstance. If you think that sounds like a strange basis for a film: well, yeah, but its oddness is treated with deadpan wit by writer/director Quentin Dupieux, who once made a horror movie parody—2010’s Rubber—about a spare tyre that embarks on a murderous rampage.

Dupieux’s style is to create strangeness by synthesizing form and content rather than leaning on one over the other. He does not, for example, wink-wink the audience with internal allusions to the kooky nature of his story (content) nor frame it in bizarre ways (form). David Lynch might have directed Deerskin as if it were a dream; others might have treated it as a farce. Dupieux keeps a straight face.

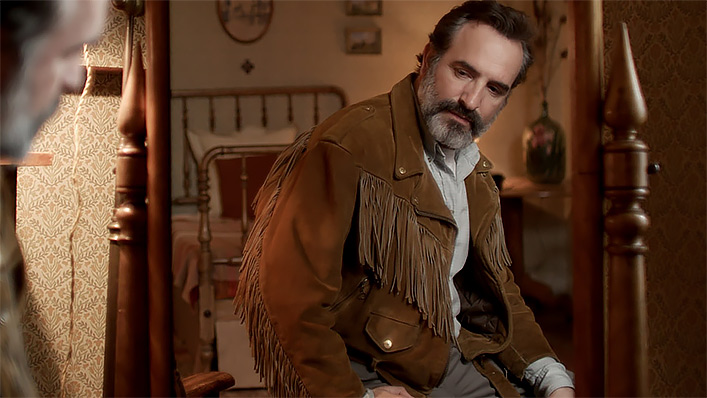

When the protagonist Georges (Jean Dujardin, best-known as the star of The Artist) acquires his deerskin jacket for a pricey sum, the man he buys it from throws in a free camcorder—which becomes as significant as the camera wielded by the protagonist in Michael Powell’s notorious thriller Peeping Tom. Sipping whiskey in a bar soon later, Georges turns to a couple of women and interrupts their conversation by asking: “you talking about my jacket?” He says it as a statement, not a question. In his head: of course they are. Everybody is.

At this point in the film certain questions beckon. Are we watching a portrait of a madman? Is this slightly pathetic fellow (played with weary stubbornness by Dujardin) experiencing a leather-scented mid-life crisis? Or is he just a daggy dude who really, really likes that jacket?

When Georges claims he’s a filmmaker, one of the women assumes he makes porn. He doesn’t, but when he returns to his hotel room he gazes lustily through his camera’s flip-out screen, giving the subject he’s filming sweet assurances such as “you look great on camera” and “we’ll make a nice team.” The subject is his jacket.

Deciding that he really will become a filmmaker, Georges’ work in progress has the narrative nuance of Harmony Korine’s perverted curio Trash Humpers, entirely composed of him filming people removing their jackets. In the second half of the film, which in its entirety runs for a lean 77 minutes, the form and content of Georges’ film-with-in-a-film morphs and mutates with the form and content of Dupieux’s in nasty ways—creating a kind of grotesque artistic inception.

Dupieux (also his own cinematographer) does funny things to Deerskin’s visual texture, matching and muting colours to create amorphous, glob-like qualities, as if elements of the frame have been camouflaged by other objects and surfaces. When Georges stands in his hotel room in a greenish button-up shirt, the shirt is a similar colour and tone to the lamp shade, which is similar to the pillow, which is a similar to the wall, and on and on we go. Scaled-back colour grading further coalesces the various elements, washing them out and enmeshing them, as if everything has been glued together using the same fabric.

In another scene at the bar, I noticed the whiskey was a similar colour and tone to the jacket, which was similar to the woody furnishings, which was…you get the point. Everything comes back to that bloody jacket. With the weirdness of this film seeping into my veins, I asked myself: is the jacket so powerful that it’s dictating the colours of its own universe? Is the jacket the film’s director?

Like in surreal works from the great Italian director Luis Bunuel, the viewer interrogates the properties of a reality that makes perfect sense to those inside it. Dupieux creates a sort of universe-building simulacra: a copy of a world that never had an original. Rubber was shits and giggles: a midnight movie to blow the mind of cinema studies students after a few bucket bongs. Deerskin is sharper, wittier, funny, and very compelling. Not quite ingenious but getting there.

In one scene Georges is sitting in bed, in the foreground of the image. But Dupieux has him blurred, keeping the shot’s literal focus on the background—on the jacket resting on a chair. It is a tantalisingly clever touch: as if the jacket were an actor requiring our attention, the director imbuing an otherwise ordinary setting with imperceptible qualities—like the villain we sort of saw but didn’t really in Leigh Whannel’s recent The Invisible Man reboot.

Flashes of innovation such as this, which play around not with general absurdity but specific filmmaking contrivances, make Deerskin one of the best and most interesting comedies of the year. You can dismiss it as pure prankerism, or use it as a way to reconsider key concepts involving dramatic and visual staging. I’ll go for the latter. It all comes back to the jacket.