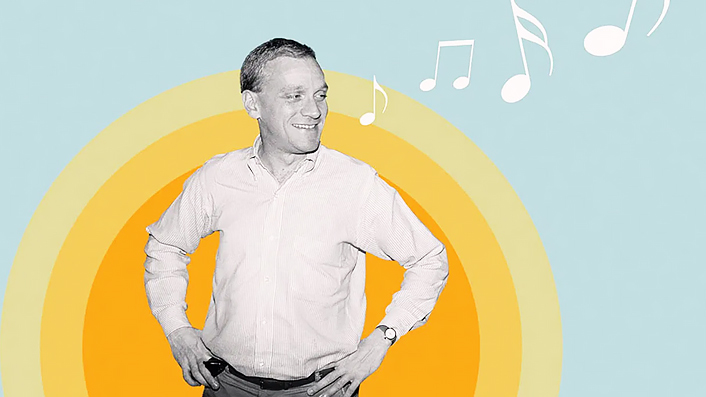

Howard is a touching tribute to the man behind Disney’s best songs

Beloved lyricist Howard Ashman, who wrote the songs for animated musicals such as Aladdin and Beauty and the Beast, gets an affectionate tribute to his life in a new documentary now streaming on Disney+.

Watch Aladdin—the 1992 animation, preferably, but the 2019 live-action remake if you must—and just try not to get its songs stuck in your head. It’s impossible, with tunes like Friend Like Me and Arabian Nights as catchy as they are expressive and melodic. Indeed, almost 30 years since the first version initially hit screens, a section of the film’s Prince Ali has proven a particularly persistent earworm. As written by Howard Ashman with his trademark lyrical smarts and musical vibrancy, the lines “Prince Ali! Fabulous he! Ali Ababwa! Genuflect! Show some respect! Down on one knee!” are as infectious and engaging as any movie ditty could hope for.

See also

* All new movies & series on Disney+

* All new streaming movies & series

By the time audiences were singing along to these tunes from their cinema seats, then again in their heads afterwards, Ashman had passed away. Consider Aladdin’s music his final parting gift, then. Alongside his Oscar-winning work on The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, the Baltimore-born talent left the world with much to remember him by from his few years at Disney alone. And, in the company’s new documentary Howard, film and musical lovers are reminded why Ashman was a giant in both fields before his death to AIDS complications aged 40.

There’s much to cover, beginning with Ashman’s childhood fondness for immersing others in a different world by putting on shows. From there, the boy who was never going to enjoy fishing grew up to start his own 1970s New York theatre with his first love, Stuart White. When, with Alan Menken, he adapted Kurt Vonnegut’s God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater into a musical, the author left a rehearsal smiling. When Menken and Ashman took on Little Shop of Horrors, they created a stage sensation that both remade a movie and spawned its own big-screen version.

Director Don Hahn paints Ashman as dedicated, meticulous and supremely skilled. When Ashman is seen giving the great Jerry Orbach notes during a Beauty and the Beast recording session, it leaves an imprint—as does the revelation that it was Ashman who chose the Divine-style look for The Little Mermaid’s Ursula. But it’s the movie’s willingness to explore not just Ashman’s professional prowess but his illness that gives Howard weight. He kept his sickness a secret for as long as possible, lest he risk 90s-era backlash for being a gay man with AIDS making kids movies, and compositions like Beauty and the Beast’s Mob Song take on a different force with that in mind. Howard reminds viewers more than once that the world lost someone special when it lost Ashman; it also reminds us that his plight at the time took its toll, and not just because of his health.

Of course, this is a touching tribute from its very first moments, with Hahn adopting a clear tone of adoration and reverence. The filmmaker produced Beauty and the Beast, so his tender documentary is grounded in real-life emotion and not just brand-mandated sentiments. Disney loves celebrating its own, though. As its filmography in recent years has demonstrated, it also loves getting as much mileage out of its hit films as possible, including those boasting Ashman’s contributions. Accordingly, this ode falls firmly in the company’s expected wheelhouse. Still, while no one utters a bad word about the Mouse House during Howard’s 94 minutes. The movie’s affectionate mood is wholly directed towards its subject, and earned.

Sign up for Flicks updates

In the same vein, Hahn doesn’t take any stylistic chances, or serve up any surprises in his approach. As Ashman’s friends, family and colleagues share their recollections about his life, their voices are layered over archival photographs and footage—of him, his work and, in particularly revelatory moments, using behind-the-scenes material from his career. There are no talking heads here, but Howard’s style and its largely birth-to-death structure are firmly standard. And yet, Hahn isn’t merely taking the easiest route.

Rather, the director does everything he can to constantly push Ashman to the fore. We look at his face. We see his stage productions. We hear his songs. More often than one might expect, too, we listen to his own thoughts from old interviews and talks. What those who knew him best have to say is a key component of the documentary, undoubtedly and inescapably; however theirs’ aren’t the main voice that Kahn or viewers are interested in. Obviously, we’ll have Ashman’s words in our heads, singing Under the Sea and Be Our Guest to ourselves, long after we finish watching.

More

See All