I’m Thinking of Endings Things is Charlie Kaufman’s take on Meet the Parents

Batshit crazy auteur Charlie Kaufman enters the horror, or horror-ish genre with this predictably weird and angsty film about a young woman meeting her partner’s parents.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things. I’m Thinking of Ending Things. I’m Thinking of Ending Things.

Those are the first words spoken in—wait for it—I’m Thinking of Ending Things, the new Netflix film from meta-fiction fabulator Charlie Kaufman, making his entry into the genre of horror or the horror-ish or the horror-esque. No category can contain the Kauf. Not romance (he wrote Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind); not longform journalism (he wrote Adaptation); not, erm, pontifications of modern theatre by way of existential rumination (he wrote and directed Synecdoche, New York).

Kaufman is one of those rare screenwriters whose films, even when they are not directed by him, feel distinctively his. The person who is thinking about ending it (I repeated that line three times at the start of this review because it just felt…right, in a Kaufman-y sort of way) is an unnamed protagonist (Jessie Buckley) who is on a weekend away with her partner Jake (Jesse Plemons).

Driving through pelting snow, they are en route to visit Jake’s mum and dad (Toni Collette and David Thewlis) who The Young Woman—as she is referred to in the credits—has not met. So: the horror of the inlaws, though this isn’t exactly Meet the Parents, or it is by way of the Kauf: more a pogo stick ride through the tumbledown town of the protagonist’s angst-riddled subconscious. If you think that sounds too far-out, you haven’t seen a Charlie Kaufman movie.

During those long stretches in the car, which take place near the beginning and near the end, the writer/director finds a compelling way of cutting through use of sound, maintaining visual continuity while verbally dislocating it. The protagonist’s stream-of-consciousness inner thoughts spill from her mind as she looks gloomily out the window, pondering her relationship, the past, future, etcetera—only for Kaufman to abruptly turn the voice-over off whenever Jake opens his mouth, forcing her to address the person in her company.

This creates a jolting stop-start rhythm, illustrating something often experienced in life but difficult to depict on screen: the interruption of a thought process. Or many thought processes. By opening her mind up to the audience, then shutting it down, then opening it up again, etcetera etcetera, Kaufman makes talking to herself feel intimate and talking to someone else feel lonely. Juxtaposing such discordant dialogue with the constant motion of the automobile adds another discrepant layer: the conversation goes nowhere while the car keeps moving.

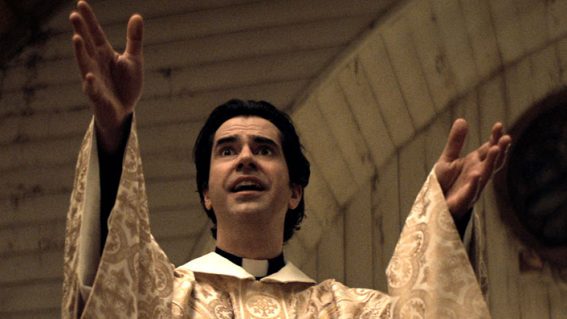

The feeling that the film is playing intellectual funny buggers ramps up when we meet Jake’s parents. They emote from the wrong reality—weird laughter, chewed up face expressions—as if they’re cartoon characters forced to deal with a live action world, thrown from flat frame to spatial universe. There is something desperate in Toni Collette’s laugh, something diabolical, something that says she’s on a fast train to hell but hasn’t arrived yet.

“Everything is not what it seems,” reads the puh-lease official description from Netflix, though everything that’s not what it seems is often what it seems—some twist, some kink in the matrix, something coming up to bend reality or at least put dog ears on it. Instead of Kaufman using meta-fiction to express the chaotic essence of I’m Thinking of Ending Things, taking reality and stirring it around and around, creating something that feels circular because it never really begins or ends (like the swirling narratives of Synecdoche, New York) the film’s last act dives into random sights and sounds that are wildly, knowingly, and almost self-defeatingly weird, predictable in broad concept (expect the unexpected!) but specifically surprising.

There’s a fine line between playfulness and purposelessness; a charitable reading would say the line here is blurred. It’s not the explosions of batshit craziness that most enthrall but the events leading up to them, when you can sense the walls of logic are going to collapse in on themselves but you can’t quite see the fold marks. If all this is intended to evoke the horror of a person trying and failing to come to terms with themselves, the film is, I suppose, a success. It’s maddening and interesting and exhausting, as it was always going to be—because you can’t contain the Kauf.