Jim Henson: Idea Man celebrates a once-in-a-lifetime creator

Premiering at Cannes, Ron Howard’s biographical documentary revisits the fascinating life and work of Jim Henson. The film does its level best to platform the restless counterculture side of Henson, says Sarah Thomson.

It’s fitting that a sense of two particular restrictions looms over Ron Howard’s Jim Henson biopic: time and permission.

Jim Henson: Idea Man, an original documentary for Disney + that has reportedly been fourteen years in the making, bears all the pros and cons you’d expect from being produced by the same suite of companies that have owned the majority of Henson’s IP since a much-publicised asset sale to The Mouse™ in 1989.

There’s incredible access to archival footage, including sketchbooks, local television appearances and a raft of Henson’s (really quite excellent) experimental animation and short filmmaking. There’s an obvious and apparently sensitive deal that’s been brokered between Disney, Howard, and the remaining living members of Henson’s immediate family—four adult children, all of whom appear on camera. There’s also the expected reticence to dig into oft-hinted-upon third dimensions of a man whose legacy’s saleability would rather steer clear from labels such as: ‘workaholic’; ‘frustratingly inscrutable’; ‘absentee father and husband’.

It’s a sanitation, a trade-off that’s always a little [sad trumpet noise] in explorations of the man that gave the world 35-odd years of intense creativity and innovation—but, look, we get it. No one wants to remind the Western world their surrogate father figure let his actual parenting slip while creating a dizzying array of worlds, characters, and giddy, felted joy.

However, we’re all (mostly) grown up now—and there’s an argument to be made that we can handle the obvious truth that simply no-one can have that kind of breakneck creative output without neglecting a few key things. And while the glimpses are brief, to be fair to Howard and the interviewed Henson children, this is probably as close as we’ve ever danced toward those truths. Hints at open relationships and strange mental struggles with capitalism whip past us as we spin through more standard biographical fare.

Within the tensions of time and permission, Howard does their level best at platforming the restless counterculture Henson, especially in earlier years, a creative fascinated by synaesthesia and eschewing any systems or oppressive ways of being. One who, let’s be honest, never wanted to make entertainment for children—and if that reads as a surprise to you, dear reader: I’ll leave most other such lovely surprises unspoiled and on the table. There will be much for you to enjoy within Howard’s near two-hour portrait.

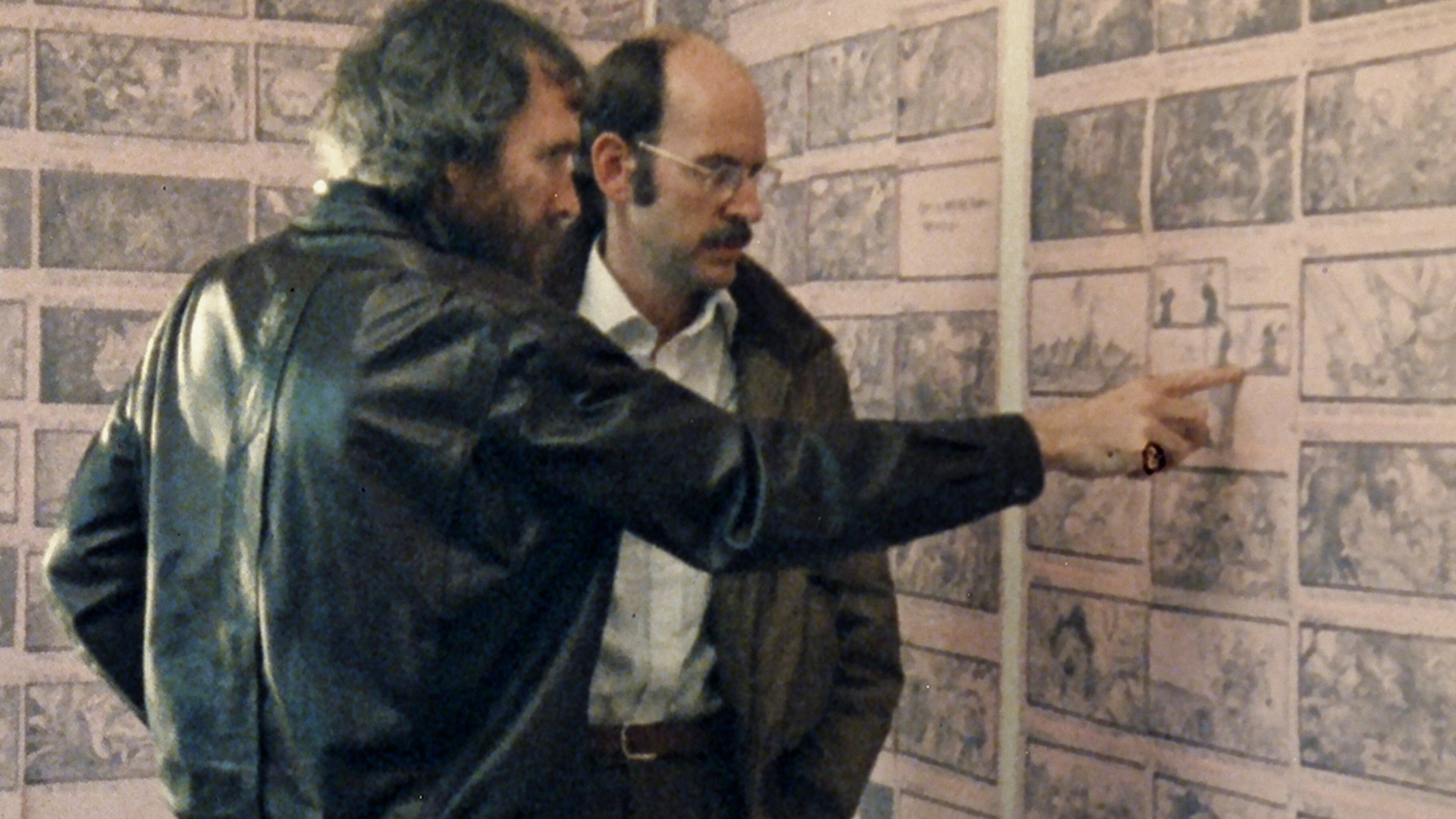

For those with Henson pre-knowledge, however, I will spoil one somewhat important thing: there’s Frank. And a good, fore-fronted amount. Relaxed and engaging, Frank Oz’s participation in Idea Man is worth the price of admission alone—offering calm, subtle insights into their collaboration, which spans from pre-Sesame Street to post-Muppet filmmaking. Often called the Abbott to Henson’s Costello (or vice versa), Oz is not known to mince words, nor to sugarcoat their time working with Henson, and Howard knows full well to let Oz’s contemplations hit hardest.

Reportedly impressed by Henson’s ability to lead creatives without bullying—and possibly seeing themselves in such a figure—Howard hones in on Henson’s 1965 short film Time Piece, itself a testament to the creator’s obsession with feeling trapped, to needing momentum, as well as Henson’s career-long positively Buñuel/ Dalí levels of film language innovation and experimentation. It’s a keen pick from the permitted catalogue and a somewhat stark metaphor for a once-in-a-lifetime creator who worked as if they needn’t sleep and whose life ran out at all too short a date.