Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is a stylised vision of expressionist angst

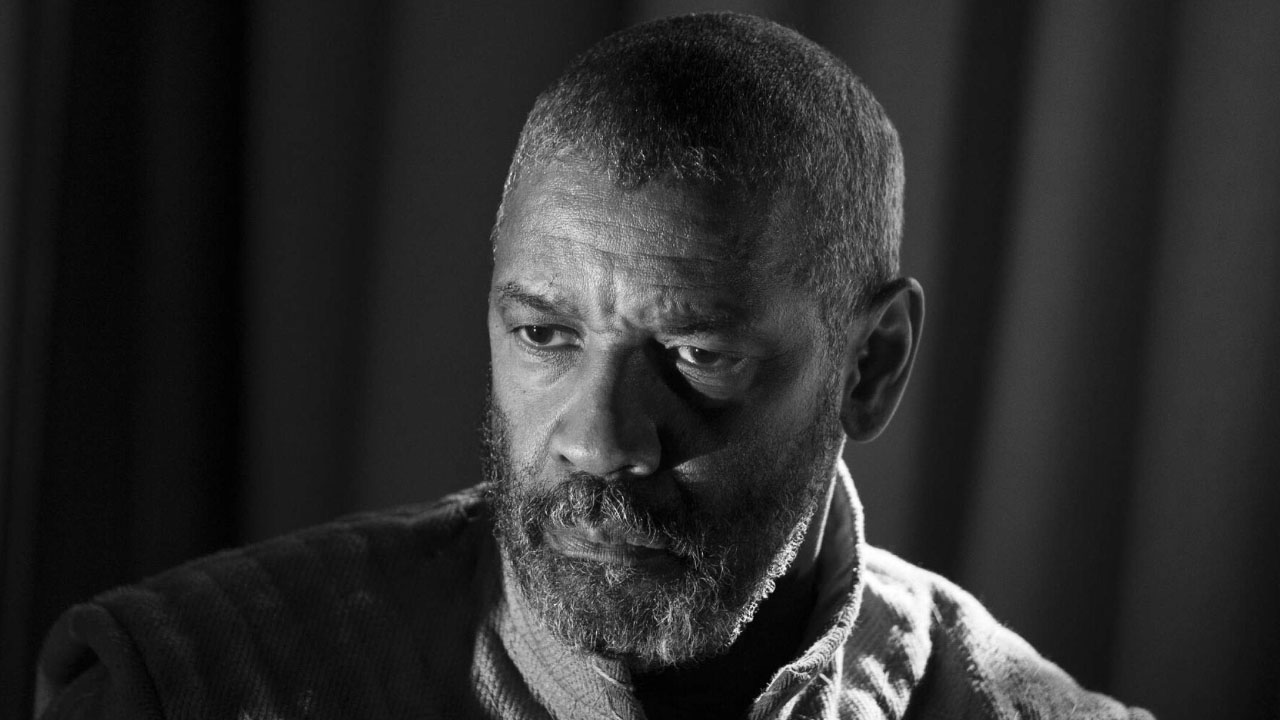

Joel Coen goes solo with his take on Shakespeare’s Scottish play, shot in black and white and starring Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand. Moody, minimalist and sharply stylish, The Tragedy of Macbeth captures lightning in a bottle, writes Adam Fresco.

It may be the first Coen brother movie, with Joel directing solo, but this spin on Shakespeare’s tragic tale has more than enough going for it to make up for Ethan’s absence.

Playing with notions of cinema versus theatricality, it’s shot entirely on a soundstage, but Bruno Delbonnel’s stunningly sharp black and white cinematography and the director’s commitment to delivering a stylised vision of expressionist angst make for a first-rate visual treat.

But the real fireworks are the actors at the tale’s beating and bloody heart. With the Macbeths played by screen greats Denzel Washington, and Coen’s real-life wife, Frances McDormand, who needs expansive locations and epic sets?

Instead, the minimalist setting only serves to enhance the powerful performances of the two leads, in a beautifully-shot monochromatic adaptation that retains the dark poetry of Shakespeare’s words, lean run-time, and air of dark menace throughout.

A script written over four hundred years ago is injected with vibrant life, utilising expressionistic lighting and sets, presented in the narrow Academy ratio that, like Robert Eggers’ similarly four-by-three, monochrome movie The Lighthouse, lends it an unsettling dreamlike quality. Think David Lynch’s nightmarish Eraserhead, only with Shakespearian verse, in a vision that exists somewhere in the collective imagination between silent-movie picture palaces and Shakespeare’s Globe.

Yet, at a lean 105 minutes, it’s a focused take on Macbeth’s inner turmoil. This sears powerful images into the imagination and drags audiences into a world in which witchcraft and political manoeuvring co-exist, in an adaptation that refuses to take anything too literally. Instead, The Tragedy of Macbeth aims to bring the subtext of Shakespeare’s dark and violent morality tale to the fore.

One major alteration Coen makes to the original text is rolling the three witches into one, with Kathryn Hunter delivering a terrific turn. Hunter more than delivers on the promise she showed as Timon in the 2019 Royal Shakespeare Company Live production of Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens. Hunter proves inspired casting as a manifestation of natural and supernatural forces combined. Morphing from rock to raven, Hunter is a surreal Wyrd Sister, preying on Macbeth’s vanity and lust for power, setting tragedy in motion by foretelling that one day he will be King.

Standing in the way of that prophecy is reigning monarch King Duncan, played with ferocious control by Irish acting powerhouse, Brendan Gleeson. When Macbeth returns from the battlefield to tell his waiting wife of the promise that he will one day be King, Lady Macbeth seizes on the opportunity to help nudge destiny along. It’s an old story, oft-told on stage, screen, and in school classrooms, but the secret to making this tale worth the retelling is in the core cast. As Lady Macbeth, McDormand is outstanding. Her character isn’t second fiddle to her husband, nor a devilish cartoon character sat on Macbeth’s shoulder whispering temptations, but a politically astute pragmatist, with her steely gaze set firmly on the Scottish throne.

In a male-dominated day and age, it’s Macbeth’s wife who stokes an ambition made palpable by Washington’s initially understated performance. At first, he refuses his wife’s call to seize the throne, but in time he allows her words to fan the fire of ruthless desire. It’s a choice that, once made, sets him on a bloody journey towards betrayal, madness, and tragedy ultimately of his own making.

For some, Denzel’s subdued start as the Thane may feel out of step with more bombastic renderings of Shakespeare’s “Scottish Play”, but it’s a level-headed beginning that allows for maximum contrast when he loses, by turn, his grip, his temper, his friends, respect, and mind. Together, McDormand and Washington deliver a pair of power-players, motivated by a deep-seated desire to seize the crown, but never able to quiet their inner consciences enough to ignore the moral repercussions of their actions, as violence begets yet more chaos, and the death count of innocents swells.

Surrounding McDormand and Washington are a superb cast. Alex Hassell ably plays Ross as a politically motivated opportunist, eager to please whichever political dog is on top. Corey Hawkins makes Macduff a force for Macbeth to reckon with, whilst Harry Melling proves a dynamic Malcolm, and Bertie Carvel lends Banquo depth and empathy as Macbeth’s loyal, yet much-maligned, best friend.

Of all the Coen Brothers’ back catalogue, it’s most reminiscent of their black-and-white visual tour de force, The Man Who Wasn’t There. Coen, through Delbonnel’s expert camerawork, finds powerful visual references, taking inspiration from past screen versions—from Orson Welles’ stark, monochrome 1948 Macbeth, to Kurosawa’s 1957 Japanese Samurai version, Throne of Blood. Replete with moody shadow-play, reminiscent of 1940s Hollywood film noir classics, every frame becomes a stark painting of the moral choices facing characters doomed to tragic ends by their own inner faults.

Of all Shakespeare’s plays, Macbeth is the leanest, meanest, and most modern in terms of pace, action, character motivation, and tension-building narrative. Coen doesn’t disappoint. Moody, minimalist, and sharply stylish, The Tragedy of Macbeth captures lightning in a bottle, with two actors at the top of their game, delivering a masterclass on how, seeking absolute power, Shakespeare’s famed couple find absolute corruption.