Adrien Brody’s mug is beautifully mopey in the atmospheric but slow Chapelwaite

The latest of maaaany Stephen King adaptations, Chapelwaite plonks a sea captain’s grieving family in a 19th-century haunted house. But the Stan spook-fest might not be enough to keep viewers interested, writes Luke Buckmaster.

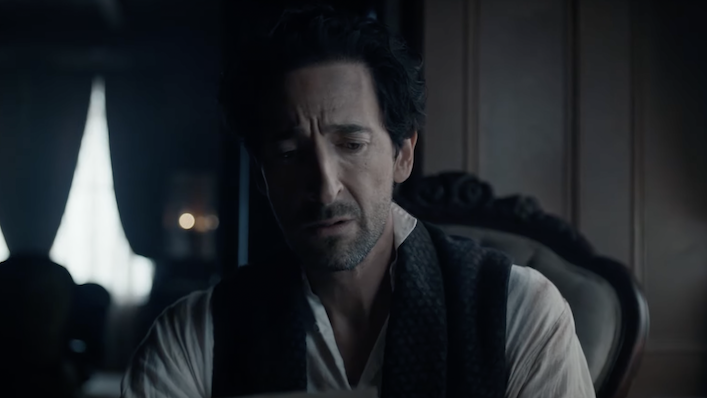

What is the best way to describe Adrien Brody: as the kind of man who looks like he fell out of an Edvard Munch painting, or who rented a Lincoln outfit from a costume shop and never returned it? The bloke looks good in a top hat, that’s for sure, as the latest Stephen King adaptation Chapelwaite—a.k.a. King adaptation no. two million fifty seven—reminds us. Brody can deliver a line like “hark, who goes there?” like it’s nobody’s business, and looks very much at home behind the wheel of a ship sailing around in the 19th century.

See also

* All new movies & series on Stan

* All new streaming movies & series

This is where we meet Brody’s character—Captain Charles Boone—and his three young children, shortly after the passing of their mother. Her death is conveniently timed, narratively speaking, to coincide with the death of Boone’s cousin, who has bequeathed him a creaky old estate (called Chapelwaite) where much of the series takes place. Underneath a rich starry night sky, bobbing about on the sea, Boone informs his fam that they have inherited a “saw mill and a house”, and therefore will give the whole ‘living on land’ thing a go.

This sets the series up within a relatable framework; who among us hasn’t inherited a saw mill once upon a midnight dreary? When the family arrive at the property the caretaker informs Boone that his cousin died of grief, to which the Cap responds: “We all carry grief, it’s rarely fatal.” Translation: “I know what that word means, you can see it stamped across my face.”

Indeed, no dialogue is necessary to reiterate this point. Intense sadness swells out of Brody’s eyes, down his long nose and whippet-like face, ensconcing the actor in a thick funk of melancholia perfectly synced to the show’s gothic aesthetics. The directors go hard on gloomy fog-infused atmospheria, à la mist rising from the ground, a deathly musty colour scheme, and various creepy looking things decorating the opening credits, such as tombstones and the sort of old portraits that look like the eyes of the subject will follow you across the room.

Chapelwaite certainly looks the part. It’s elegantly shot and edited. It’s classy, like Brody. The big question is whether the deliberate mood and slow-moving pace can sustain itself over 10 episodes—a difficult task at the best of times, exacerbated by the fact that the source material, Jerusalem’s Lot, is only a few dozen pages.

Four episodes in, the series is struggling to sustain my interest and I feel I’ve had enough sad Brody to last a lifetime—or at least until his next picture. The prospect of watching another six hours feels deflating. With so much content from so many places vying from our attention, I doubt I’ll keep rappin’ and tappin’ at Boone’s chamber door.

The story quietly takes the form of a “new family in the neighbourhood” tale, matching the difficulties in the Boone’s fitting in—given townspeople blame their family for causing a plague—with the recurring inference of something ghostly or supernatural potentially at play. It involves the hiring of a governess (Emily Hampshire) who is keen to build rapport with the kids, but is also a non-fiction author interested in spending time at the creepy estate for inspiration to write a magazine feature.

Chapelwaite‘s storyline builds slowly, like a piece of music creeeeeeping towards crescendo, only to suddenly indulge in the kind of gnarly images that are beyond cliché in the horror genre. Think creepy looking girls in white dresses who pop up out of nowhere, freak people out for a bit, then disappear as quickly as they arrived.

A more effective—and certainly far grosser—visual motif arrives in the squidgy form of worms. Boone initially observes these little slithering frenemies in the cellar after descending stairs which, of course, creak loudly, as if emitting the cries of doomed souls trapped inside the timber. The worms take on extra eeriness when fused with some good old-fashioned body horror. In one scene, showing Brody examining his sad face in the mirror, he notices a…no, wait, I won’t go there. In a series as long and slow as this, best to savour the surprises of its few-and-far-between high-impact moments. Including the ones involving freaky children.