Park Chan-Wook’s Decision To Leave is a beguiling work of modern-day noir

Direct from its Cannes film festival screenings, Rory Doherty got swept up in Decision To Leave: a Hitchcockian tale of a lonely detective and his icy femme fatale.

Decision to Leave

Park Chan-wook’s films regularly focus on outsiders to regular society, those trapped within restrictive roles and consumed with singular, destructive ideals. But what makes his work so reliably transcendent are the unorthodox relationships that appear between the people who recognise their own alienation in others.

Whether it’s border guards on either side of the Korean border, two night-prowling vampires, or a wealthy heiress and her duplicitous lady-in-waiting; connections between those trying to find peace in a hostile world are what elevates Park’s work above visuals and bursts of violence.

Decision to Leave, a procedural-romance riffing on Hitchcock and femme fatales, may appear more minor a work from the Korean maestro, but beneath the story’s twists and turns lies another deception—that the mystery leading us from scene to scene is all in service of a romantic and affecting tale of what actions (and which people) we’re drawn to when we feel irreparably estranged from our modern world.

The unorthodox relationship in this film is potentially the one we’re most familiar with—an intimacy between a male detective and his female suspect. Hae-joon (Park Hae-il, who had a supporting role in Bong Joon-ho’s masterful procedural Memories of Murder) is a workaholic insomniac, a detective with a punishing commute and a clinical-feeling marriage.

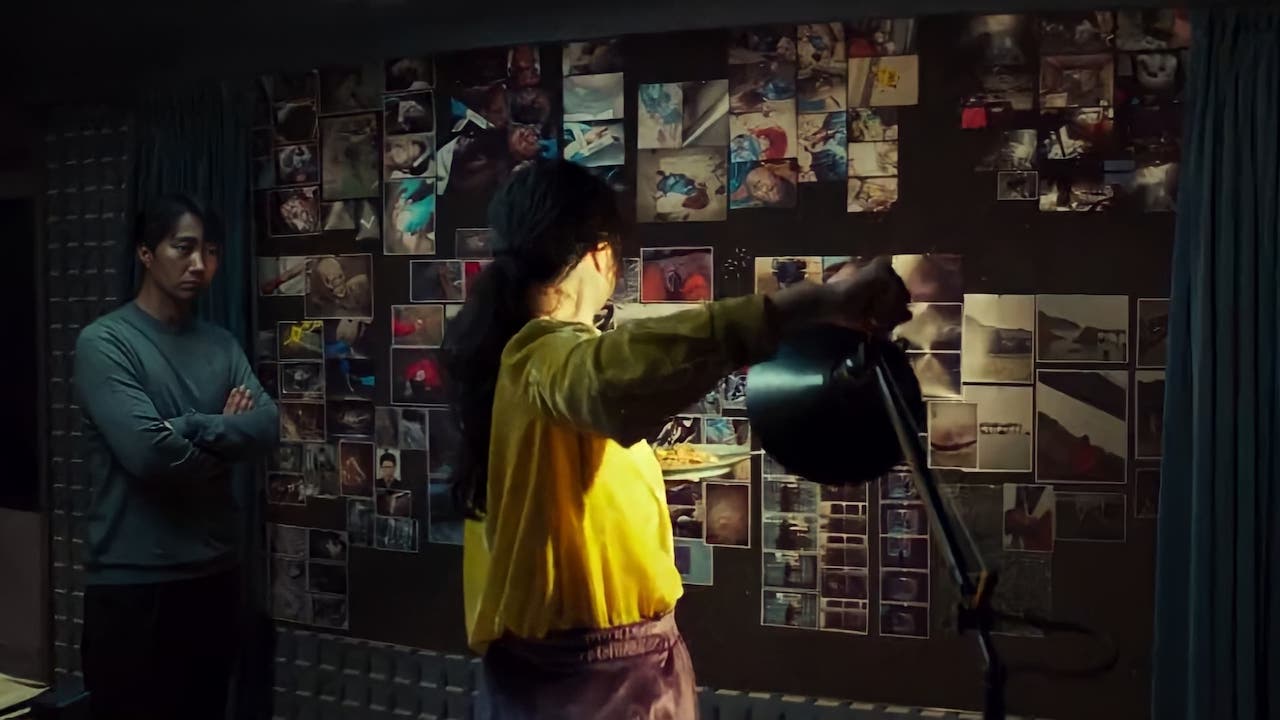

When a hiker falls from atop a mountain, fingers start pointing to the corpse’s Chinese wife, Seo-rae (a completely confident and cool Tang Wei). As you’d expect, there’s something beguiling about her, but other than the perfectly constructed style, Park keeps you invested in a familiar narrative through his central pair acknowledging themselves that they’re existing in a type of story, one that has a history of predecessors and a wealth of derivatives.

Every time we see Seo-rae watching a cheap Korean melodrama we’re reminded she knows she’s playing a game with Hae-joon, acting an archetype she’s relying on him to be familiar with as well. Body language and what we communicate physically, whether calculated or unwittingly, is a huge part of both crime and romance narratives; when Hae-joon comments that a murder suspect couldn’t be a killer because of the way he fights, we start to wonder about what information he and Seo-rae are transmitting to each other without words.

What sets this apart from most other Park Chan-wook movies is the abundance of modern technology; smartwatches, recording apps, GPS trackers, and plot-relevant step counters. The presence of modernity isn’t just to freshen up a story Hitchcock explored 60 years ago, it highlights the despondency that consumes our characters—sure, there’s an app for everything you’ll ever need, but what if using them only reaffirms how ineffectual we feel as people?

Hae-joon is drawn to Seo-rae because he notes she has a “classical” vibe, and she herself comments on what sets him apart from other modern people. In a world that feels suffocating and passionless, something as old-fashioned as a detective-suspect affair has an undeniable appeal.

Focusing just on character does a disservice to how much of a visual feast Decision to Leave is. From beginning to end, you’re reminded of the unparalleled dynamism that fills the director’s work; with impactful sound design, gorgeous framing, and genius edits (just as it’s mentioned how blowflies lay eggs on cadavers, we cut to Hae-joon cracking an egg into a pan). Decision to Leave may not be as flashy or sumptuous as some of his other work, but in his first collaboration with cinematographer Kim Ji-yong, there’s plenty of sweeping tracking shots, severe pans and impossible perspectives (from a dead man’s eyes or under a morgue sheet) to pore over.

If there’s anything worthy of complaint, the building momentum of Decision to Leave is so effective that the script, penned by Park and regular co-writer Jeong Seo-kyeong, feels a little shaky in the final stretch. The fast-paced reveals in the climax juggle more than a bit with information, meaning it’s all less slick in its house-of-cards-assembling than The Handmaiden.

But it sticks the landing perfectly, with a resounding resolution that hammers home the emotional throughline of the story. This is a film about two people deeply uncomfortable with their place in the modern world, who through each other have had to grapple with both meanings to the act of leaving; what happens when we leave someone, and what of ourselves we leave behind.