Phil Tippett is Frankenstein and Mad God is his painstaking, visionary monster

You can see every year and scrap of material that went into making Phil Tippett’s Mad God, a nightmarish assembly of apocalyptic sequences. Rory Doherty worships at the stop-motion altar.

With a rerelease of Robocop and another Jurassic Park movie now in cinemas, you could say Mad God, a stop-motion animation from Phil Tippett, the visionary VFX artist behind those classics and more, couldn’t have been released at a better time. Tippett would probably strongly disagree with you, as he’s been fighting to complete the film for decades.

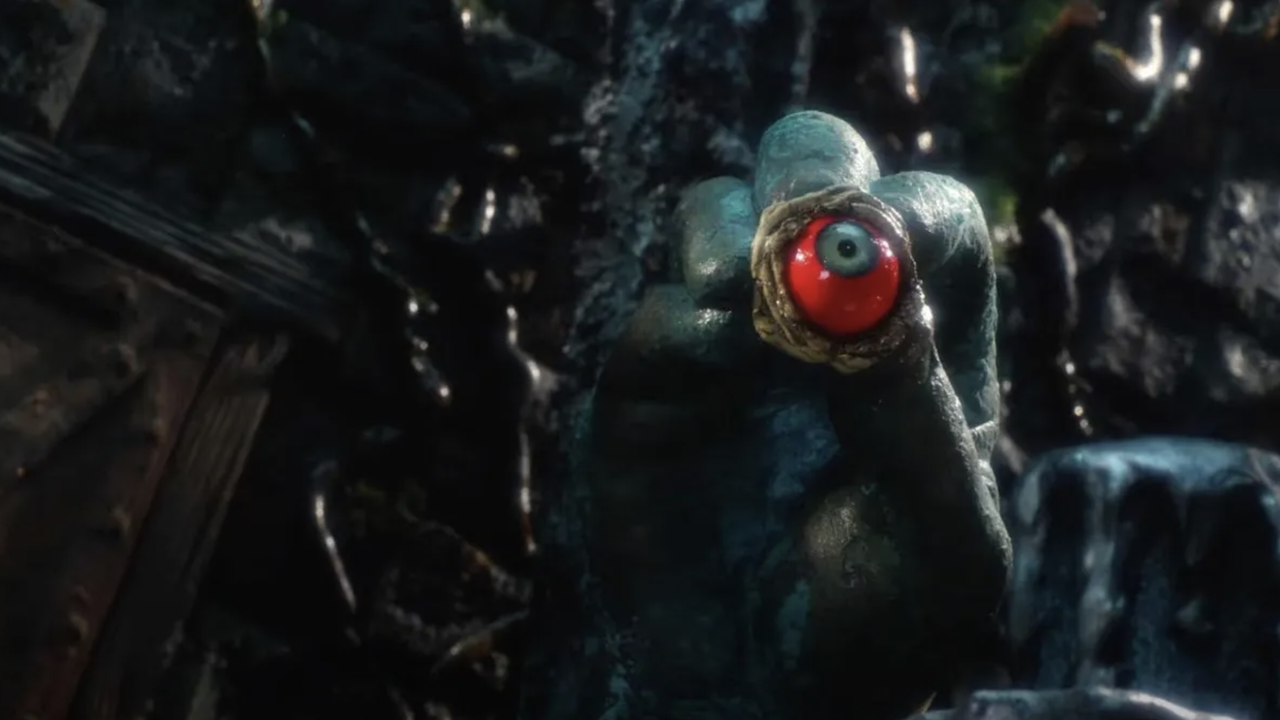

The culmination of volunteer work and Kickstarter funds, Mad God is finally unleashed on the world. “Unleashed” is the operative word, as the film feels like a primordial, post-apocalyptic, living thing, an electric blend of the industrial and the arcane that delves into a world long abandoned through primarily stop-motion, but also features CG effects, animatronics, and live-action footage.

It’s easier to describe Mad God as a production than a narrative, as everything that went into making it, the relentless craft and effort, is so clearly on display throughout the runtime, while the story itself is more obscure and diverting. With no dialogue, we only have searing visuals and grunting noises to guide our Dante-esque descent from a war-torn surface-world to the subterranean layers of deserted civilizations and perverse experimentation: spaces that feel simultaneously vast and claustrophobic.

We may recognise images or symbols, but they’re presented in such a distorted, contextless manner that the journey of Mad God is one of trying to make sense of the world we’re being shown. But there’s no doubt it’s one where everything stable from our reality has supercharged and inverted. The Old Gods are dead, long live…a potato with human teeth.

But while Mad God’s plot is minimal, it’s also evocative. A gas-masked figure credited as The Assassin witnesses a whole lot of full-on, messed-up goings-on, but largely minds his own business as he pushes ahead with a mission that remains uncertain until a midpoint diverts and recontextualizes the narrative. This approach allows the different sequences to soak, letting ideas float around our heads before congealing into concrete shape.

In the film’s most absorbing sequence, humanoid workers are created wholecloth out of discarded materials, all identically resembling a Frankenstein creation. They perform arduous and seemingly inconsequential labour only to be absent-mindedly cast aside or destroyed with little care for the humanity with which the animators have effectively imbued them. At another point, live-action surgeons perform a gruesome autopsy to an eager audience, filmed with the aesthetics of silent-era cinema that make the living, breathing people on screen feel less recognisably human than the claymation labourers.

Fascism, revolution, anarchy and alchemy all make appearances in nebulous but potent ways throughout the film; they always feel distinct and rarely homogenise. It’s a testament to the uniqueness of Tippett’s vision that everything feels teeming with life and plays with an undercurrent of ideas.

His work on FX-heavy blockbusters share key similarities; the Paul Verhoeven vehicles RoboCop and Starship Troopers enjoy a wealth of highly charged commentaries in the form of political satire, and Jurassic Park had the monumental task of bringing to life creatures no-one had ever witnessed interact with the real world before. Even Starship Troopers evokes empathy for its alien lifeforms in a similar way to the hideous but pitiable beings that populate Mad God.

Structural issues appear, however, in how Mad God’s ideas are all arranged. Even though the animation is wise to change up its narrative drive, from the midpoint on the momentum it built up starts to falter. By the end, the discovery that Tippett expanded three short films into a full feature is of little surprise.

It’s both a good and a bad thing that the sequences feel loosely connected and distinct. On the one hand the detached structural approach hammers home how disintegrated and without order the world has become; on the other it means, despite how compelling an individual scene will be, it’s understandable if viewers start to lose their way.

Thankfully, the individual scenes have so much power to them, Mad God doesn’t feel flimsy—rather bursting at the seams. To submit to Tippett’s gorgeous nightmare fuel is to experience the insidious horror that comes when you think too long about the depths of the ocean, of the conditions that manifest grotesque creatures, but also the miserable quality of life such animals must endure.

There’s no victorious moral authority reshaping the world in the correct way here: according to Mad God, survival is overrated. Just enjoy the end of the world while you can.