Queen & Slim is an outlaw romance for our fractious age

An outlaw romance for our fractious age, Queen & Slim challenges expectations even if it sometimes misses the mark, writes critic Craig Mathieson.

Predicated on a rich visual style and the crucible of American racism, Queen & Slim is a series of journeys: a road movie running for safety, a love story taking shape in the moment, and the private transformation of people into martyrs. Directed by Melina Matsoukas with a defining touch – usually for the better, but occasionally the worse – this story of a thrown together couple fleeing the retributive hand of the law traverses moods.

It can be languorous and lacerating, so there are dream-like moments and scenes of high drama in heady proximity. The picture’s ambitions inoculate it against easy genres and that makes sense. The people thrust into the headlines we see are often more complex than the summary they’re afforded, so why can’t a movie about those people be equally involved?

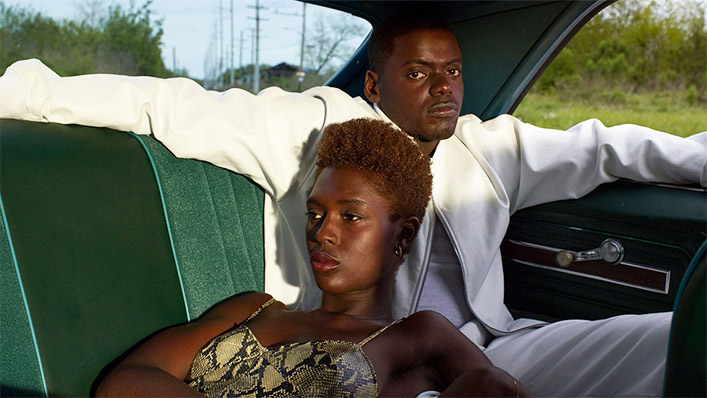

When we first meet Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith) and Slim (Daniel Kaluuya) – these nicknames and their real names aren’t provided until the closing coda – their last-minute Tinder date in an Ohio diner is withering away. She’s had a bad day and wanted company, but isn’t impressed with him, a slight he coolly accepts even as he makes the case for his own identity. But when he’s driving her home afterwards a police car siren changes everything.

“You got any warrants,” Queen demands as they pull over. This is their reality of being black in America. Any assumption can be pulled out from under you, any safeguard voided, any encounter could be dangerous. In a masterfully tense scene that’s what transpires – scared by unchecked aggression, they leave the scene as fugitives, with shots fired and hopes dashed. “TRUSTGOD” reads his licence plate. It didn’t help.

“I’m not the criminal,” he says. “You are now,” she replies.” The pair are unwitting escapees, duly deemed “armed and dangerous” by the police as they try to figure out how not to get cornered and killed. They travel south, with roadside anthropology and broad hints of the society that trapped them, notably black prison inmates working a field. Their notoriety is a hindrance and a help. Like a modern day underground railway, some people provide shelter and assistance. The hardest to convince is Queen’s Uncle Earl (Bokeem Woodbine), a troubled and unmoved presence in New Orleans whose backstory with his niece is one of several stories unfurled along the way. The clarity they’re afforded is distinctly mixed.

The screenplay by Lena Waithe updates fugitive tales even as the duo become attuned to each other. It suggests that the true act of defiance is not hard-edged resistance, but a willingness to embrace and enjoy life, particularly when it’s at risk of being curtailed. Matsoukas amplifies this. Making her feature debut after helming Beyoncé’s Formation video clip and episodes of Insecure, she surrounds the protagonists with glorious imagery. A sojourn in a rural blues bar in a southern state is a symphony of red surrounding the pair’s first dance; you might not believe such an art-directed location exists, but the film brings it alive as black skin is lit and photographed with sumptuous care.

Unfortunately a late, lengthy sequence, conflating sex and protest, wildly misses the mark – but it’s unavoidable because Queen & Slim is in immersive thrall to iconic images. It wants to show how ordinary people become publicly owned figures, and to do that it uses the striking and sublime to considerable effect. There’s no way out of that for Queen, Slim, or the movie.