Review: Ida

In this era of filmmaking where narrative bloat seems to be the norm, it’s always heartening to see a filmmaker who understands, and continues to practice, the virtue of paring down to essentials and cutting through the bullshit. One such filmmaker is Pawel Pawlikowski, who’s already demonstrated his predilection for wrapping stories up in under 90 minutes with economical gems like Last Resort and My Summer of Love.

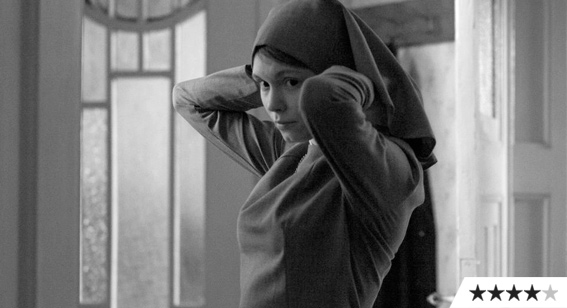

Ida finds the Warsaw-born director returning to his home country for a black-and-white period piece that’s easily one of the more visually striking, meticulously composed – and hypnotically still – films of the year. Transporting the viewer back to 1961 rural Poland, the film follows Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska), a convent-raised orphan who discovers the grim truth about what happened to her family during the Nazi Occupation of World War II.

A certain portentousness is unavoidable in the material and execution: it’s a film that tackles religion, national identity and wartime horrors, and photographed in the square, once-standard, now-novel academy ratio that begs comparison to the austere formalism of European miserablist heavyweights such as Bresson, Bergman, Tarr et al. But there’s also a subtle wryness that prevents Ida from buckling under the gloom, particularly when Anna is paired with her only living relative, Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a lonely, alcoholic judge with Communist ties. Furthermore, the scenes where Anna is given a taste of freedom in the company of a jazz musician provide lovely, tenderly observed moments of respite.

A quiet, sparsely plotted film that grows in memory.