The Iron Claw transforms chest-beating sports baloney into great drama

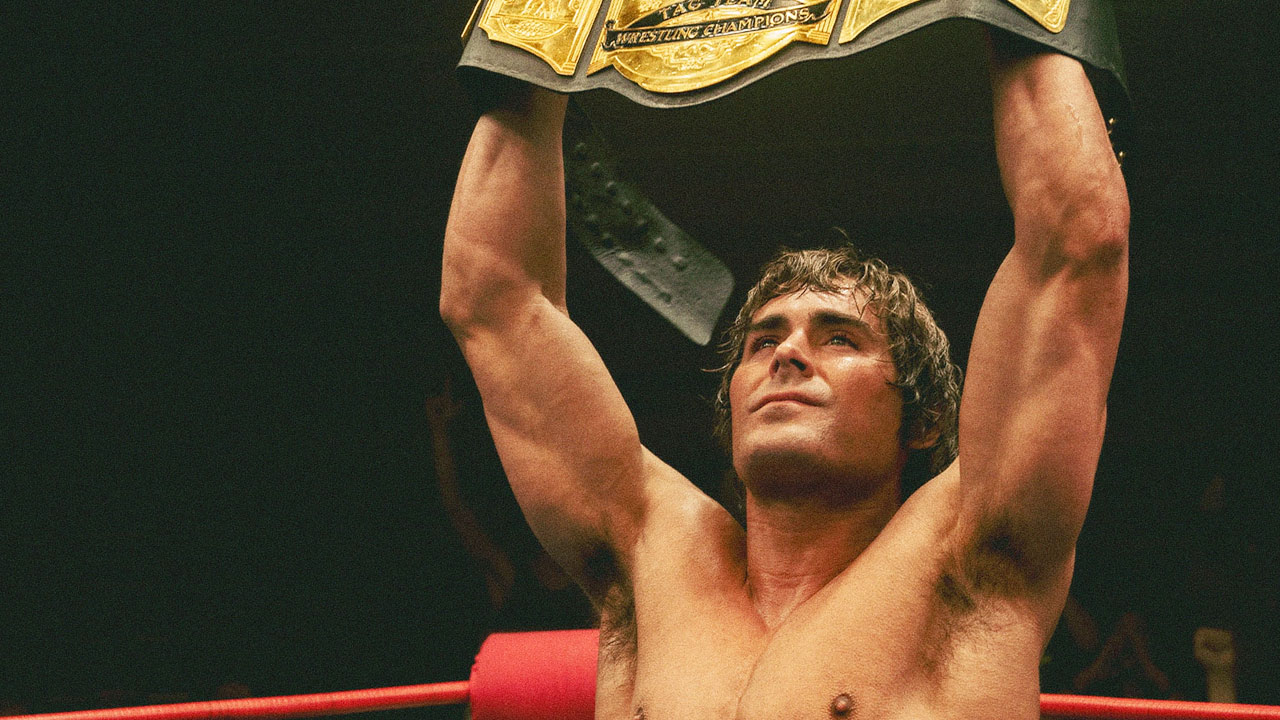

The wrestling world’s tragic “Von Erich Curse” gets retold in subtle, melancholic detail in Sean Durkin’s The Iron Claw. Here’s Luke Buckmaster’s review, singling out Zac Efron’s grizzly lead performance for praise.

The Iron Claw

The chest-beating, rah-rah-rah, “win at all costs” sports movie ethos gets a cold hard reality check in writer/director Sean Durkin’s sensitively drawn portrait of real-life wrestlers the Von Erich brothers, each of whom dreamt of becoming the NWA World Heavyweight Champion. Some succeeded, but it’s fate rather than destiny that defines their sad story, filled with death and sorrow.

“Fate” and “destiny” both imply predetermined outcomes, but the former is tanged in tragedy: something suffered rather than achieved. Early in The Iron Claw, Durkin (whose oeuvre includes Martha Marcy May Marlene—one of the best films about cults) floats the idea, via dialogue assigned to one of the brothers—Zac Efron’s Kevin—that the family may be cursed. But by what exactly? The answer may lie in another suggestion, inferred rather than spoken: that this is perhaps a narrative about sons trapped inside their father’s dreams. If it’s not also about toxic masculinity, it’s in an adjacent space, gently skewering passé notions of manhood.

Visually the film is modest, with a spongey timeworn veneer, although it has one head-turning special effect: Efron. In the Bad Neighbours and Baywatch movies the star looked like he couldn’t get much more ripped, but here he’s something else: a human beefcake, strapping and sturdy as all get-out, with a body like Schwarzenegger circa Pumping Iron, and a lantern-jawed face banged up like an old catcher’s mitt.

It doesn’t take long for Efron’s performance to feel totally grounded and lived in. By the end of the film it struck me as a wonderful portrayal—not of somebody trying to achieve something per se, but a person wrestling with themselves as a product of the other, bent and shaped by social constructs and formative influences, particularly those from his father Fritz (Holt McCallany), a quintessential old school “my way or the highway” patriarch. Born of a different era, as they say, though almost certainly a problematic presence no matter the time period.

We’re not surprised to learn that Kevin’s family—which also includes brothers David (Harris Dickinson), Mike (Stanley Simons), and Kerry (Jeremy Allen White), and mother Doris (Maura Tierney)—eat lots of bacon and sausages, and spend lots of time talking about winning. The film’s introductory scenes, presented in monochrome, provide an early key to its meaning, progressing from Raging Bull-like vision of a sweaty face in the ring to a gentler moment in a carpark with Fritz and his kids. Fritz has rented a Cadillac, telling Doris that if he wants to be a bigshot wrestler, he should start acting like one, because in his head he’s “almost there”—on the precipice of something.

What if that precipice lasted not only for the rest of his life, but was passed down to his kids—also doomed to be stuck in the purgatory of “almost there”? What if the dream itself is the curse? These ideas rise gradually, informed by Durkin’s empathetic and carefully calibrated perspectives.

In some ways The Iron Claw feels intimately tuned to its subjects, and in others, healthily detached, in that Durkin doesn’t judge them for their failures, look down on them for their choices, or get too swept up in their appetites and longings. Nor does the film drip pathos from an open wound, like Darren Arronofsky’s great drama The Wrestler, which soaks up all its protagonist’s hopelessness, makes it clear that he’s too far gone, too trapped inside himself to start again. Its title song—written by Bruce Springsteen—spells everything out: “if you’ve ever seen a one trick pony then you’ve seen me.”

The Iron Claw is more subtle, the melancholia coming incrementally. It’s like a gradual rise in a song with no chorus. The final act, and especially the final scene, expands those ideas around the self as a product of things hardcoded into us from birth. This film has a hard-fought sense of optimism, but it’s there, inspiring in a poignant way.