Wild doco series The Lady and the Dale investigates a serial con artist and automotive entrepreneur

A portrait of a transgender pioneer who was also at the centre of a larger than life crime saga, this documentary (now streaming on BINGE) is a fascinating story with many angles, writes critic Craig Mathieson.

BINGE’s HBO docuseries The Lady and the Dale features a serial con artist, an ambitious automotive entrepreneur who predates Elon Musk, a Machiavellian figure spinning the media, and a trans woman whose public profile in the 1970s was groundbreaking. That these figures are all the same person—one Geraldine Elizabeth Carmichael—is both a testament to the complexity of an individual and a sizable challenge to storytellers.

No strand here is complete without the influence of another. Thankfully directors Nick Cammilleri and Zackary Drucker are able to tie them together with not just a deft structure, but also empathy. The narrative never gets away from them.

See also

* All new streaming movies & series

* Best new movies and TV series on BINGE

After an opening sting about the Dale, a three-wheeled car whose economical operation was meant to revolutionise the 1970s, the linear focus is the lady, who was born in 1927 and grew up in Indiana as Jerry Dean Michael, going through multiple marriages and scams according to an FBI file that grew rapidly.

“I was not what I could have been,” a family member was told, and the way that speaks to both her identity and ambition is typical of shifting layers of self-perception and eventually public judgment that would take hold. By the 1960s a marriage had stuck, and a passel of children—several of whom extensively recount their loving memories here—were part of a fugitive life. California, the transition to ‘Liz’ Carmichael along with motherhood, and the purchase of the Dale prototype in 1974, were the next step.

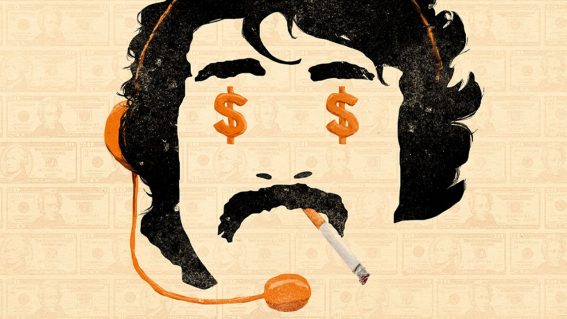

The voices heard here include Carmichael’s tape-recorded opinions and the testimony of those who worked with and against her. They’re illustrated by Cinemation Studio with a bouncy, deliberately retro style that animates still images so that heads bounce from side to side and cars leap about on static backgrounds. You couldn’t get further from a noir-inflected look—there’s a touch of children’s cut-and-paste to it—but the collage technique also matches the unfolding events, which sit between outlandish and sadly necessary.

Carmichael’s 20th Century Motor Car Company (the name suggests a Hollywood studio, the ultimate dream maker) intended to wipe out Big Auto, even as NASA design experts rubbed shoulders with gangsters. It was a wild operation; Carmichael had two bodyguards, until one “accidentally” shot the other four times.

The business machinations are outlandish, but Cammilleri and Drucker—the latter a trans woman, activist and television creative—always view Carmichael as a nuanced individual. She made huge claims about the Dale, which was meant to get approximately 30 kilometres to the litre during the Arab oil embargo, but as is often the case the line between dreamer and schemer is a fine one. Carmichael’s own words are perhaps not as illustrative as those around her, even if it’s the L.A. newshounds—with definite shades of Anchorman—who investigated her story and made her transitioning part of a public and legal judgment. It’s merely an addendum, but typical of this series, that Carmichael’s foe, TV reporter Dick Carlson, just happens to be the father of Fox News blowhard Tucker Carlson.

Latter episodes make good use of transgender historians to detail a world that was not just unaccepting of Carmichael, but a risk to her safety, and what people who needed to transition had to go through—and experiment with—due to a lack of a formal framework. Carmichael was involved in numerous legal cases, where she often defended herself with successful legal insight (and possibly a bribe), and one of her victories was getting legally recognised as a woman.

Ultimately The Lady and the Dale, which follows I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, The Vow, and McMillions as impressive HBO documentary titles, leaves you to decide which part of its subject takes precedence: the master sales artist or the loving mother; the visionary or the grifter. You can rank them however you like, because the defining achievement here is to recognise that one life can contain them all and more.