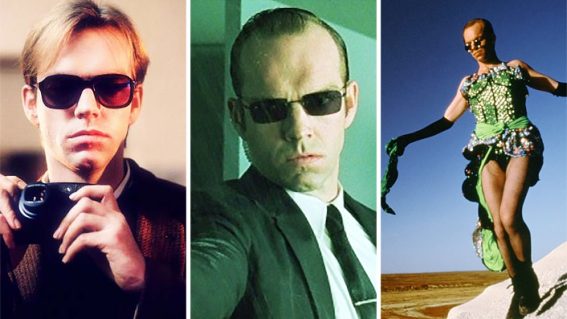

The Nightingale is unforgettable – but not without its flaws

Jennifer Kent’s harrowing follow-up to The Babadook shows Australia’s colonial past as a frontier war. It’s an unforgettable film, but not without its flaws, writes critic Craig Mathieson.

In The Nightingale power’s only natural form is violence. It is 1825 and in a British outpost in then Van Diemen’s Land, the commanding officer, Lieutenant Hawkins (Sam Claflin), has been exterminating the Aboriginal population under the guise of subjugation. For pleasure he holds a former Irish convict as his indentured slave, raping Clare (Aisling Franciosi) as if simply asserting his property rights. When her husband Aidan (Michael Sheasby), also Irish and also previously transported, objects it creates a transgression that is punished with violence so extreme, so expansive, that it is inexplicable, at least until you realise that it’s simply the norm.

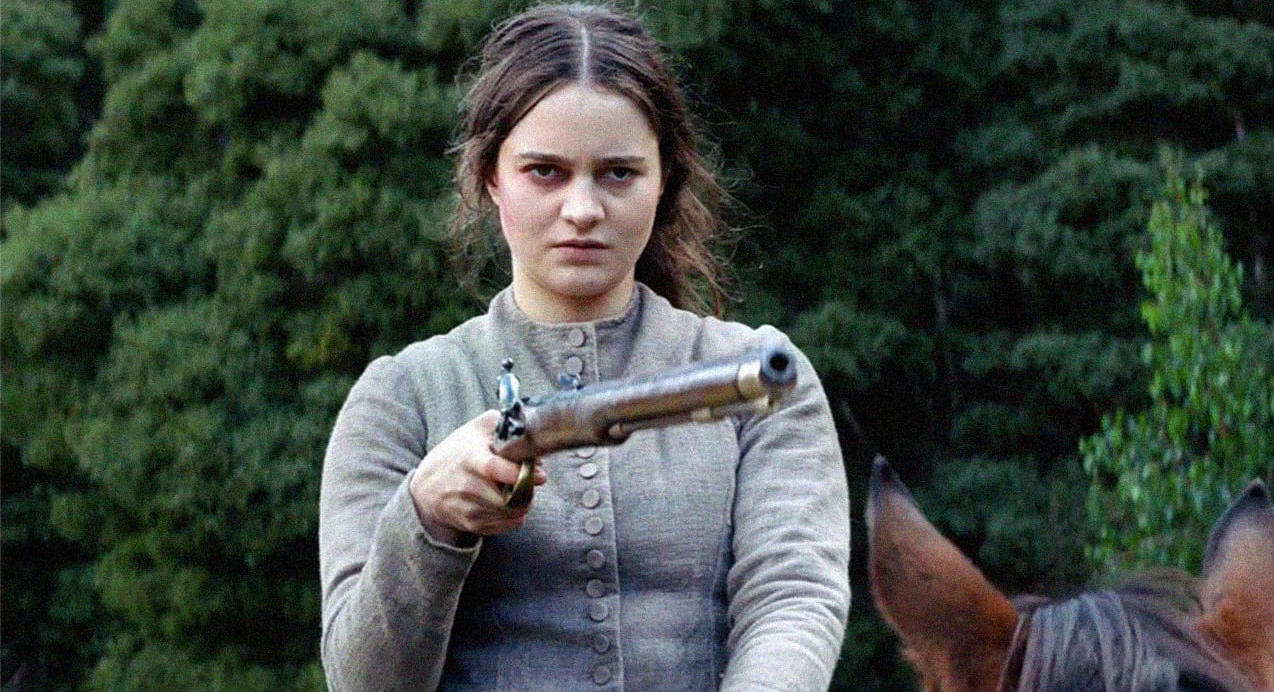

Eschewing the breadth of a wide-screen frame, writer and director Jennifer Kent shows colonialism as an act of destruction, whether on a public or private scale. It warps everyone connected to it or merely present. Wronged beyond reason, Clare’s response is to seek retribution, pursuing Hawkins when he decamps for Launceston to plead his case for a promotion.

The officer travels with a harried retinue, includes Aboriginal guide Charlie (Charlie Jampijinpa Brown) and a sergeant defined by his obsequiousness and butchery, Ruse (Damon Herriman). Meanwhile Clare coerces another Tasmanian Aboriginal, Billy (Baykali Ganambarr) to lead her through the cloud-covered landscape, where the trees divide into knotted branches and each turn brings the possibility of crimes that will never be judged.

Covered in blood and armed, Clare is a fitting image of revenge for a netherworld where corpses hang from trees. But Kent is not interested in what revenge requires, but what remains after it can no longer persist. The connection between Clare and Billy in central to The Nightingale, and at first she treats him with the same racist dismissiveness that she has endured.

Drained of empathy, Clare barely notices that Billy has also endured unspeakable trauma that has engulfed him, his family, his tribe and his way of life. As much as they find common ground, the narrative is from Clare’s perspective, and sometimes there’s a shorthand for Billy’s state that has to get complex feelings down to a single sentence.

Kent’s success here is in what she shows. In extreme moments the camera’s gaze is always steady, allowing no diversion from what unfolds. There are moments of sustained horror – where everything that is defiled about this world seems concentrated to a terrible pitch – that shun the comforts of genre or consolation.

There’s a tapestry of languages to accentuate the different strata and the performances are first-rate, whether in the form of Claflin’s monstrousness or the barbed retorts that Franciosi and Ganambarr allow to breach their character’s scars. That the film pushes past an obvious finale is testament to its ambition, and a reminder that flaws linger beneath its shocking narrative. The final cruelty of the many contained in The Nightingale are the limits it reaches.