The Predator is an action-packed sci-fi with a fun 80s party vibe

Homages to the 1980s are a dime a dozen these days, but here’s a film that salutes the decade in sentiment as much as aesthetic. Fifty-six year-old writer/director Shane Black, who had a small on-screen role in the original 1987 Predator (released the same year his first film as a writer, Lethal Weapon, became a hit) is a kind of trash-talking Peter Pan auteur: the action junkie and banter-maker who never grew up, and whose style is synonymous with the era he professionally came of age.

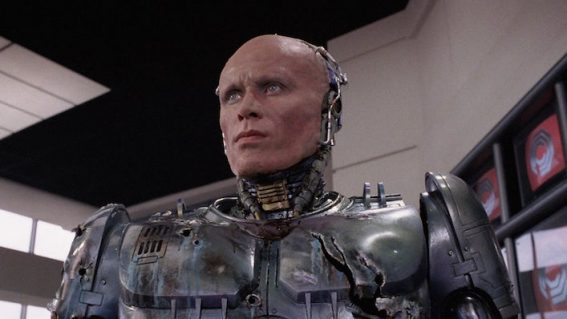

When we see the titular creature stomping around in a research facility early in Black’s The Predator, it’s obvious the filmmaker (whose other films as writer/director include Iron Man 3, The Nice Guys and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang) doesn’t mind if we think of this ridiculous looking thing as a person in a monster suit. He reiterates the point by setting the film during Halloween, when makeup is gnarly but the mood is festive.

The first word in the title The Predator (which is the fifth Predator sequel – including spin-offs) is important. It implies this thing has fame, notoriety, stature. There are two moments in the opening minutes when characters pick up and study the Predator mask. First is ex-military sniper Quinn (Boyd Holbrook) after happening upon a crash-landed alien ship; then his young son with autism Rory (Jacob Tremblay) after opening a postal delivery box. In both instances it is as much a discovery for the characters as a recognition of an iconoclastic franchise.

Black doesn’t pussyfoot around, barely ten seconds elapsing before the sight of a spaceship spitting laser beams. The director then scrambles his own plotlines, like a child happily messing up his own puzzle. The story jumps from Quinn to Rory then to evolutionary biologist Dr Casey Brackett (token female Olivia Munn), then back to Rory then back to Quinn then back to Rory.

It seems likely the boy will become the protagonist, but instead Black hovers around a group of PTSD-afflicted enemies of the state dubbed ‘The Loonies’ (Trevante Rhodes, Keegan-Michael Key, Thomas Jane, Alfie Allen and Augusto Aguilera). An escaped Predator who literally makes heads roll is a big enough concern – before a second alien emerges with unclear motives.

The group of jiving fugitives take the mickey out of the commotion around them and even, to a point, the franchise itself, riffing on how labelling the villain a ‘Predator’ is a misnomer – given it hunts for sport rather than exists by preying upon other organisms. The dialogue entertainingly falls victim to single voice syndrome, whereby different characters feel like parts of the same person (that person being Shane Black).

Black is more self-aware (acknowledging conventions) than postmodern (drawing attention to them). The director would prefer to have a slightly dodgy looking monster viewers can chuckle about then a scary creation that induces genuine fear. Thus for the CGI – and some of the sets, including spaceship interiors that resemble Play-Doh – his instruction was clearly to err on the side of ‘too fake’ rather than ‘real’. Better to be schlockly than overly serious.

The humour in The Predator feels almost pathological in its relentless ability to mine high drama for low-key banter. If Black made a film about the Titanic, the passengers would be cracking jokes and settling petty scores while they slid into the arms of hypothermia and death. The original film is a terrific mood piece: an intensely atmospheric survival in the wilderness story with a serious message about how all the muscles in the world can’t protect you when you’re out-monstered by Mother Nature. Rather than attempt to recreate that rich jungle feeling, the sequels have generally translated its midnight mood into midnight movies – which is far from the same thing.

The Predator‘s monster mash party vibe is genuinely retro rather than retro in a showboating and chic way (like Thor: Ragnarok) or in a way that raids childhood toy collections for hits of endorphin-releasing nostalgia (like Ready Player One). It is unusual for a franchise film as high profile as this to be so heavily infused with the personality and idiosyncrasies of its writer/director, which alone is worthy of recognition. The lunatic Shane Black is very much in charge of the asylum.