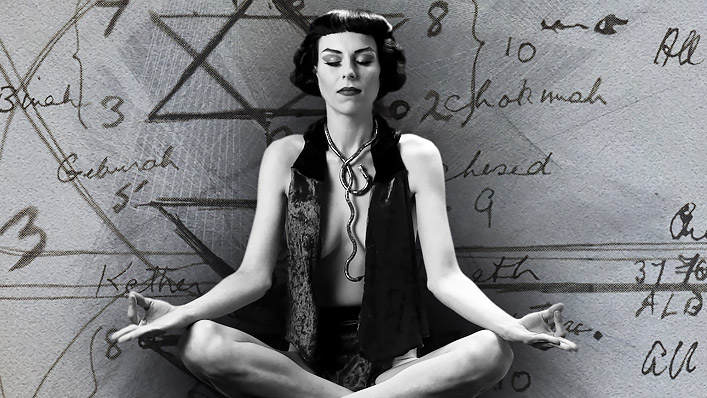

The Witch of Kings Cross is a must-see documentary about a pioneering artist

Influential artist and self-professed witch Rosaleen Norton is a unique figure in the cultural landscape and the subject of an excellent new Australian documentary, which is now on digital release. Here’s critic Sarah Ward’s review.

When any past or present figure finally gets the attention they deserve, it sparks an obvious question: why? In Rosaleen Norton’s case, the documentary that thrusts her back into the spotlight firmly answers that query. Australia has long been a conservative country, and no one should be under any illusions otherwise—so guessing how the nation’s press and police reacted to a self-proclaimed witch in the 1950s isn’t difficult.

See also:

* All movies now playing in cinemas

* All new streaming movies & series

To stress the point, The Witch of Kings Cross uses newspaper headlines. This tactic isn’t new, but director Sonia Bible must’ve had fun picking which snippets to include. Words such as “obscene”, “sex magic” and “witchcraft” feature frequently, decrying Norton again and again, and so does a two-word phrase that’s downright laughable and yet also oh-so-telling. “Girl artist”, the media badged her, wielding the term with a sense of novelty and condemnation in tandem. If Norton had dutifully conformed to prevailing expectations of women at the time, perhaps her gender wouldn’t have earned a mention; of course, that’s something we’ll never know.

Streaming platforms now use “strong female lead” as a category, but so-called polite society hasn’t always been fond of women who proudly carve their own paths. As The Witch of Kings Cross demonstrates, Norton easily fits the label. Thanks to the insights gleaned through her diaries and journals, which form a large part of Bible’s film, it’s easy to imagine that she would’ve laughed it off—just as she repeatedly eschewed attempts to impose conventions, norms and definitions upon her life.

Using a savvy mix of archival materials, dramatic recreations and modern-day interviews with experts and those who knew her, The Witch of Kings Cross steps through Norton’s story. Vivid details arise often, and linger even when more follow. Born in New Zealand, Norton moved to Sydney when she was eight, but refused to sleep indoors. To scare off anyone who might enter the tent set up in her backyard, she filled it with insects. For her first exhibition, she hitchhiked to Melbourne with a cat named Jeffrey lurking in her bag.

As comes up more than once, her love of drinking tea was as strong as her devotion to the Greek god Pan. This level of minutiae paints a lively picture, with no facet of Norton’s life ever treated like a mere tidbit. All those headlines were happy to be reductive, but Bible is committed to compiling a fascinating, expansive and well-rounded portrait.

There’s much to cover, including Norton’s embrace of the occult, trance magic and sex magic, which filters through in her work and also attracted the tabloids. The Witch of Kings Cross is at its best when it lets its subject’s words and images do the talking. While the documentary chronicles the scandals that kept garnering public attention—which say more about the response to Norton than anything else—it gives over as many of its frames as possible to the artist’s own musings and work. On painting after painting, the camera soaks in every stroke, colour, figure and symbol, making the audience wish they were seeing them face to face, in a gallery, with all the time in the world to take in their wonders.

Just minutes into the documentary, viewers should also find themselves pondering when a biopic might also traverse this story. That isn’t a criticism of Bible’s film, which constantly proves evocative and conveys a clear sense of its central figure. Rather, it simply doesn’t take long to hope that Norton, her exploits and her unyielding quest to remain true to herself will all earn more than just the 75 minutes this movie directs their way.

That initial question, “why?”, can’t be shaken. It’s apparent why Norton became so infamous during her lifetime, and just as evident why she demands her time in the spotlight again now, 42 years after her 1979 death to colon cancer. But it’s impossible not to wonder why this cycle of denunciation and then reappraisal has become far too familiar.

There’s nothing routine about The Witch of Kings Cross—not even its moody dramatisations earn the term—but wishing that it could just focus on Norton as a pioneering artist who lived her life her way is understandable. Alas, history didn’t allow her story to play out as such, and neither can this excellent and informative documentary.