Transcendent Bowie doco Moonage Daydream uses only archive footage to keep the enigma alive

Freak out in Moonage Daydream, the David Bowie estate’s first official documentary, put together with voyeuristic wonder by Brett Morgen. Rory Doherty found it long, loud, and fabulous.

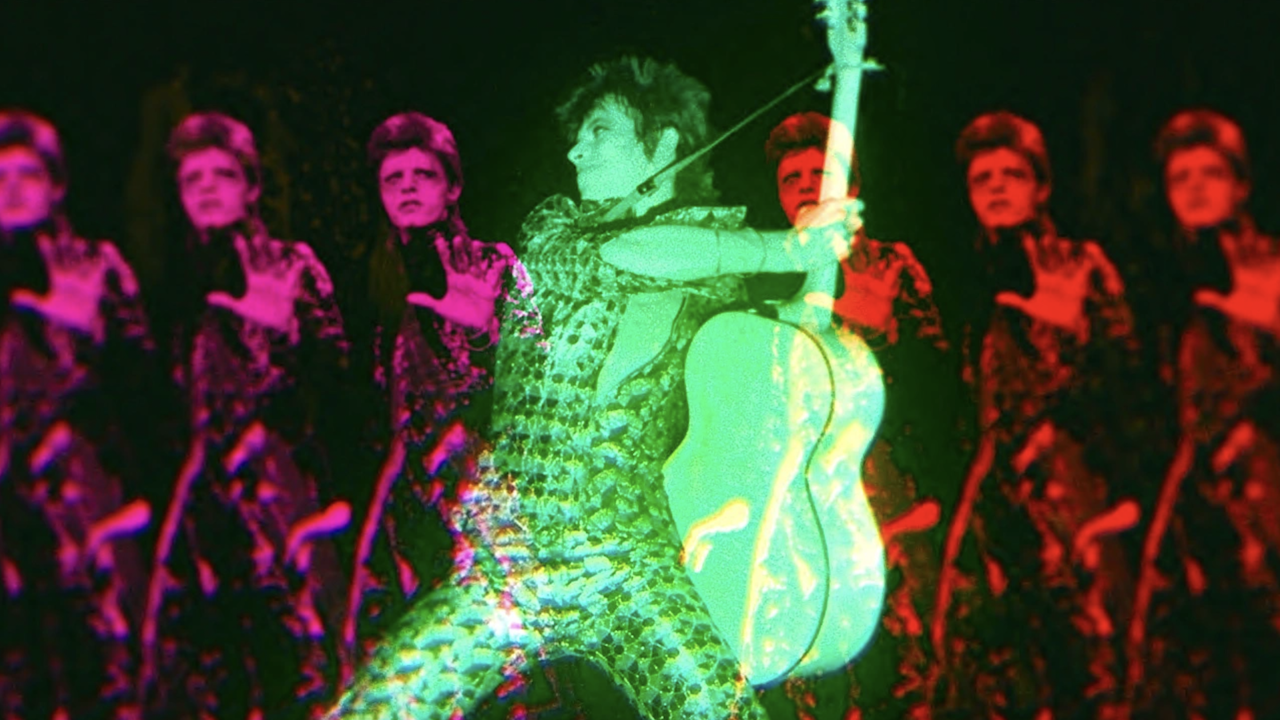

How do you grapple with the enormity of Bowie, both as an individual and in terms of his titanic legacy? Brett Morgen, the filmmaker behind Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, makes an admirable attempt here at figuring out Bowie’s true self—through only archive concert footage, music videos, and interviews throughout his career. No talking heads. No voiceover. We try to unpack the real David Bowie using only times when he was performing (for crowds or the camera).

It seems paradoxical, but Moonage Daydream pulls it off due to a couple of factors. Firstly, you don’t quite get how extensive the footage will be going in. In the first commission from the Bowie estate, Morgen has been given unprecedented access to archival footage, gorgeously restored. When frantically laid out in a two-hour-plus documentary, it only illustrates how exhaustive the wealth of available recordings must have been.

We see Bowie onstage in very public performances from a sidelined, backstage view, which communicates with immediate clarity this is going to be a more personal look at the star than other attempts (like last year’s unfortunate Stardust) could dream of being. But is anything truly candid when you’re aware a camera is on you?

The other way Moonage Daydream is so successful is the fact that Morgen is self-consciously investigating the trouble with trying to decode someone only from the outside in. As the realisation that we’re only getting glimpses to a performative self, the film feels more panicked, throwing an onslaught of noise and colour at the audience to convey how difficult it is to understand an enigmatic man who had an unparalleled legacy.

Just like the frenzied teen concert-goers who open the film, reaching up into the darkness for a chance to make contact with Bowie, Morgen signals our own collective obsession with the man unlike anything that had come before, and the tragedy of not having him around anymore. As the camera perennially orbits around the glimmering artist, you feel like we’re also trapped in his gravitational pull; unable to escape or decide how close we get to him.

With the documentarian allying himself with his audience, you feel watching the film like you yourself have been a lifelong fan of the Brixton-born rock star, even if your knowledge of his discography is more scattered. Despite the loudness of everything, the structure of the film is largely simple; we move through Bowie’s career, how the mood and style of each era was formed, with relevant, if slight, digressions into his personal and emotional worlds.

An artist’s identity starts to manifest as we move through phases that were about the manifestation of an artist’s identity, which for the most part keeps the film from feeling restrictively linear and pedestrian. Slight problems appear retrospectively when you realise how much time was spent on his 70s personas, with little insight into his 21st-century career and, most surprisingly, how his final albums confronted his own mortality.

When viewed holistically, Moonage Daydream can appear a little unbalanced, prioritising some of Bowie’s self-reflexive artistic choices over others which could have ended the film with more resonance than it does. The last moments feel like a tribute band ending the night on an obscure number rather than a crowd-pleasing banger, as Morgen highlights quotes from Bowie that, considering how insightful and mature a speaker he was, feel a little insipid and pithy.

Clips from cinema from the 20s through 50s and visual flairs beating out the rhythm of his formative works establish his influences and unpack the building blocks of his biggest hits. The doc’s maximalist approach borders on too exhausting at a couple points—and 140 minutes is definitely a bit too long—but by and large it all feels transcendent. As we learn of how obsessed with the celluloid image Bowie was, the varying quality of the archive recordings takes on extra resonance, and it’s astonishing how good the restored music videos look on a big screen.

But the film can be lo-fi when it needs to; when talking about how stripped-back his Berlin years were, we’re shown Bowie’s life only in still photos. Provocative, intimate, and a whole lot of other adjectives that don’t do him justice, Bowie’s image is shown in Moonage Daydream in blistering totality.