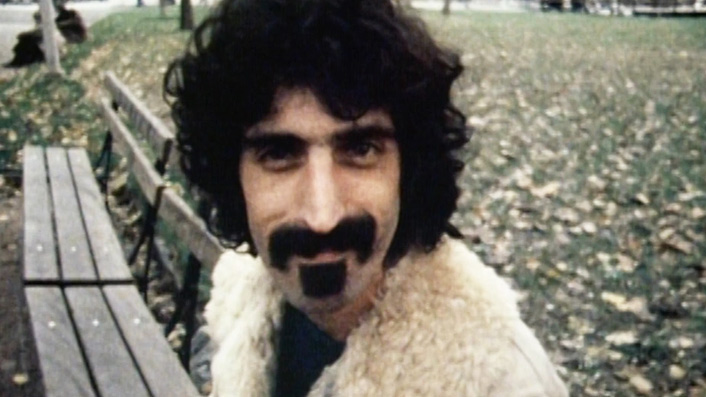

Zappa’s saving grace is its footage from the legendary muso’s personal archive

Now playing in select cinemas, Zappa documents the life and work of legendary musician Frank Zappa. It has a wealth of incredible footage—which, writes Amelia Berry, proves to be the film’s saving grace.

To a lot of people, Frank Zappa is more moustache than man. An icon, known for an idea of musical weirdness and radicalism, probably more than any one piece of music in particular. Going into Alex Winter’s new career-spanning documentary, you might expect to come away with some fresh understanding of the musician behind the myth. Instead, Zappa leans hard into Frank Zappa the troubled artist, the difficult genius.

See also:

* All new streaming movies & series

* All movies now playing in cinemas

* The 10 best music documentaries so far in the 21st century

While the film delivers a couple of touching and revealing interviews (particularly with Zappa’s wife Gail and Mothers of Invention percussionist Ruth Underwood), largely what we’re treated to are the same few lines about Zappa over and over. Cold to the point of cruel in his personal life, but oh boy was his music beautiful. Steve Vai even delivers the old cliche of alt-rock hagiography that Zappa “could have written hit songs all day if he wanted to. He just didn’t want to”.

Zappa’s saving grace, however, is the wealth of incredible footage from the artist’s own meticulous personal archive. Granted unprecedented access to the archive, Alex Winter spent two years preserving and restoring material before production even began on the documentary, and that loving care and attention shines through.

Highlights include Zappa’s own edit of his parents’ wedding video, some beautiful early concert footage of the Mothers of Invention “freaking out”, and a lot of really out-there claymation from long-time Zappa collaborator Bruce Bickford. Winter and editor Mike Nichols even do their best to incorporate Frank Zappa’s goofy sense of humour into the editing and sound design, adding a winking silliness to even Zappa’s childhood interest in the local mustard gas factory.

For a man that released over sixty studio albums in his lifetime, it’s not surprising that a lot of Zappa’s work is passed over fairly quickly. Fans may be disappointed to see, however, that the 1970s are skipped over almost entirely.

While the segments in the film showing Zappa’s ‘60s heyday edge slightly over into Austin Powers territory (complete with striped pants bum slaps and lewd banana gags), the real meat comes in Zappa’s last decade before his death in 1993. His fight against music censorship and the implementation of ‘parental advisory’ warnings, his desire to run for President against Bush Snr., and his bizarre relationship with the Czech Republic’s post-Velvet Revolution government, are easily the richest and most interesting part of the film, hinting at a political consciousness for Zappa that moves beyond “drugs are for losers”.

Ultimately, your enjoyment of Zappa is going to depend a lot on how much you enjoy spending time with Frank Zappa himself. Between the archival footage of Zappa performing, his conducting works for orchestra, and Ruth Underwood’s exquisite performance of ‘The Black Page’ filmed especially for this documentary, the music in Zappa is of such variety and quality that even those so-so on Zappa ought to get a lot out of it.

By the end of the film though, returning from these musical interludes to hear Zappa once again glibly rattle through his personal bugbears becomes quite grating. He doesn’t care whether you like his music. No musicians are up to his exacting standard. Drugs are for chumps. By the end of the film, it’s tempting to think that maybe the ‘troubled artist’ is really all there is to Frank Zappa.