How a new generation of filmmakers defined 21st century Australian cinema

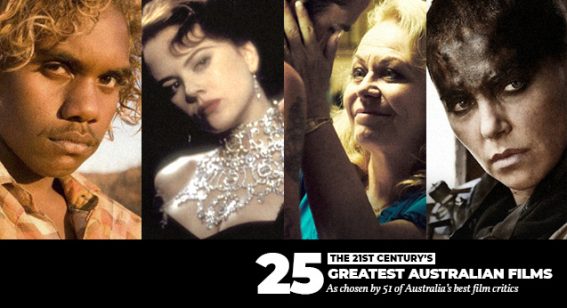

In the largest poll of Australian film critics in history, Flicks has identified their choices for the greatest Australian films of the 21st century so far. What do these films say about our artists and our industry? Sarah Ward reflects on how a new generation of filmmakers have defined contemporary Australian cinema.

A suburban matriarch training her icy glare at her sons. Two Indigenous teenagers exchanging awkward, affectionate glances amidst Australia’s outback landscape. The slicing of flesh as an incarcerated criminal tries to wrangle a transfer to a different prison wing. A mother embracing her son while screaming in terror, petrified by a pop-up book popping real fear into her life. The door to an old bank creaking to a close, with known murderers and their next victim on the other side.

Stunning sights, all of them. They all rank among Australian cinema’s standout images over the past 18 years – images of menace, struggle, brutality, terror and gruesome horror. They’re the visuals that have defined the country’s filmmaking since the dawn of the 21st century, painting a portrait of the nation one frame at a time. Some speak to fictional ills, anxieties and emotions; others take their inspiration from reality.

Our film poll coverage

* The 25 greatest Australian films of the new century

* How every critic voted

* Analysis: How a new generation defined 21st century Australian cinema

* Eight things you probably didn’t know about Mad Max: Fury Road

More than that, and more importantly for the country’s evolving cinema landscape, every one is the product of a first-time director. In David Michôd’s crime saga Animal Kingdom, Warwick Thornton’s outback romance Samson & Delilah, Andrew Dominik’s underworld biopic Chopper, Jennifer Kent’s housebound horror The Babadook and Justin Kurzel’s insidiously unnerving true-crime drama Snowtown, the future of nation’s filmmaking came into focus.

Across seven films by six filmmakers, Australian cinema gained a new voice from 2000 onwards

Unsurprisingly, all five sit in the top ten of our survey of 21st century Australian cinema – not only flying the flag for the country’s new breed of directing talent, but proving their impact over the last two decades. Indeed, Thornton achieved the astonishing feat of earning two places in the top ten, with Sweet Country also receiving a spot. And while Ivan Sen’s Mystery Road may have marked his fourth feature, he belongs in the same company.

Australian cinema: the next generation

Across seven films by six filmmakers, Australian cinema gained a new voice from 2000 onwards. It built, film by film; however if there was a movie that unleashed the call, it was Chopper in 2000. With his portrait of the notorious – and notoriously charming – real-life hard man, as portrayed so memorably by an against-type Eric Bana, Andrew Dominik crafted an effort that proved both distinctively twisted and distinctively Australian, while also commenting on our obsession with crime and fame. Chopper is dark, slick and styled in no one else’s image, with Dominik continuing in the same mould with his US efforts, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and Killing Them Softly.

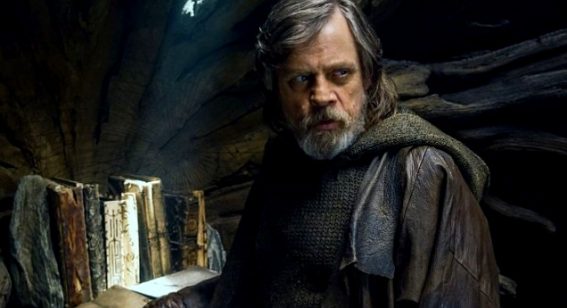

If Chopper unleashed a rallying cry, fellow crime effort Animal Kingdom answered it. David Michôd’s debut delves into the depths of a fictional Melbourne family determined to survive by any means, as overseen by Jacki Weaver’s manipulative Janine ‘Smurf’ Cody in an Oscar-nominated performance. As rare as it is for an Australian actor to earn an Academy Award nod for an Australian feature, it’s the confidence and command of Animal Kingdom that feels rarer still, in a film that earns near career-best performances out of its ensemble lineup of Ben Mendelsohn, Joel Edgerton, Guy Pearce, Sullivan Stapleton and then-newcomer James Frecheville. Michôd stepped into a familiar genre but carved his own path – as he did with his underrated dystopian second effort The Rover, this time starring Robert Pattinson.

Sign up for Flicks updates

Crime also paid for Justin Kurzel, but in a manner that pushed buttons more than almost any Australian film that came before it. Walkouts were common during Snowtown sessions, increasing as it sank further into the ghastly details of one of the worst crimes in the country’s history. A movie about a smiling serial killer preying upon the impressionable, recruiting teenagers to his murderous cause, and leading both animals and people to a cruel, torturous end shouldn’t make for easy viewing, but Kurzel amplified the discomfort in his take on the infamous ‘bodies in barrels’ case. His subsequent efforts have taken him overseas – from the sublime Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard-starring Macbeth to the silly Assassin’s Creed adaptation with the same leads – but the grimness of his homegrown debut left a considerable impact.

his story of an Aboriginal stockman on the run after protecting his wife from an abusive white station owner makes a loud and forceful statement that still echoes today

It’s a visually brighter world that Warwick Thornton’s features depict – the sun-drenched Samson & Delilah, his Cannes Camera d’Or winner, as well his piercing western Sweet Country – but one no less thematically bleak. The hard-fought quest for survival that two teenage Indigenous sweethearts weather always taints their heartfelt affection with pain, even if Samson & Delilah manages to balance hope and heartbreak. In Sweet Country, however, Thornton is at his most enraged and impassioned as he trains his sights on a climate of racism that still permeates the nation. He may have set his blistering tale in 1929, but his story of an Aboriginal stockman on the run after protecting his wife from an abusive white station owner makes a loud and forceful statement that still echoes today, as it is supposed to.

Ivan Sen’s outback detective films traverse similar terrain, surveying the country with an eye for its unmistakable natural beauty, but never failing to soberly assess its festering societal woes either. Indeed, while the writer, director, producer, cinematographer and composer’s resume includes 2002’s breakout Beneath Clouds, 2009’s rarely-seen Dreamland and 2011’s Toomelah, with Mystery Road he sparked his own franchise. The exploits of Indigenous police officer Jay Swan, of Aaron Pederson’s swagger in the role, and of carving away the idea that prejudice and discrimination doesn’t shape Australia, just couldn’t be contained to one effort. In Goldstone, the character returns for a new simmering mystery – and a new chance to expose the darkness evident in the treatment of the nation’s first people – before making another comeback in the television mini-series also called Mystery Road.

There’s an undercurrent of reality in all of the above features. Even if they’re not strictly based in fact, they’re steeped in the current state of Australia today, holding a mirror to unseemly deeds and attitudes. Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook doesn’t earn that description with its narrative, but it fits within a growing cohort of films that isn’t afraid to let discord bubble through its blood. A feature about a pop-up book monster coming to life to terrorise a single mother and her six-year-old couldn’t be anything but sinister, but it’s a masterclass in tension as well as a movie with something significant to ponder. For Kent, it’s everyday horrors that shock and scare, springing from ordinary occurrences that society often happily overlooks, such as grief, isolation, loneliness and the weight of being a woman raising a child alone.

The changing of the guard

Michôd, Thornton, Dominik, Kent, Kurzel and Sen aren’t the only filmmakers shaping the face of Australian cinema over the 21st century thus far, of course. Just from Flicks’ poll, the top 25 includes six other first-timers in Sarah Watt’s Look Both Ways, Garth Davies’ Lion, Matthew Saville’s Noise, Clayton Jacobson’s Kenny and Adam Elliott’s Mary and Max. And, from filmmakers still making their early efforts, Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s Hail is his first fictional feature, while Predestination is the Spierig brothers’ third film. Moulin Rouge! is only Baz Luhrmann’s third effort, and The Dish Rob Sitch’s second. Others placed highly, though outside the top 25, include 52 Tuesdays, also Sophie Hyde’s first fictional feature, and Sleeping Beauty, the feature debut of Julia Leigh.

when George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road finally hurtled its way across screens after a 30-year gap in his post-apocalyptic franchise, it was widely commented that it seemed like the creation of a younger filmmaker

The list goes on – not replacing the old guard, but demonstrating that it is changing. And, more than that, bolstering the country’s filmmaking ranks to lead Australian cinema into the future. It might seem amusing that, when George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road finally hurtled its way across screens after a 30-year gap in his post-apocalyptic franchise, it was widely commented that it seemed like the creation of a younger filmmaker. It was meant as a compliment, however, reflecting not only the thrilling energy and technical mastery Miller demonstrated in Mad Max’s return, but the heights reached in the character’s absence.

In moulding their films after the country around them, what many of Australia’s 21st-century filmmakers are doing isn’t new. Wake in Fright might be held up as the benchmark for Australian features casting a unblinking eye over the real state of the nation, but it wasn’t new then either. It’s also apparent in the work of more experienced directors over the past 18 years, from the suburban secrets of Ray Lawrence’s Lantana, to the fiery feminist spirit of Jocelyn Moorhouse’s The Dressmaker, to the Indigenous tales told in both Rolf de Heer’s Ten Canoes and The Tracker. Still, there’s a distinctive, determined voice evident in the current crop of local efforts, as well in the next generation of directors responsible for them – one certain to echo for years to come.